In early 2018 the then Secretaries of State for Business, Greg Clark, and Digital and Culture, Matt Hancock, announced a £150 million Creative Industries Sector Deal under the rubric of the government’s Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund. Some 20 years after the reclassification of the media and cultural industries by Culture Secretary Chris Smith in a now celebrated exercise in sector ‘mapping’, the creative sector could now claim parity of government recognition and esteem, if not financial support, with the life sciences, automotive, construction and artificial intelligence sectors with whom sector deals had previously been announced.

This Sector Deal was hard won and a long time in coming: a comparable endorsement had been rejected by the Coalition government in 2013. Although modest in scale when viewed from the perspective of the £20 billion allocated to the Challenge Fund programme as a whole, the Deal agreement was nonetheless symbolically important as a sector first. Some industry leaders believe that it will pave the way for more ambitious partnerships between the state and the private sector in a future iteration, although this begs the question of what will happen to the Challenge Fund programme under the new government. Will ‘industrial strategy’ as championed by former Business Secretary Clark survive the impending government reshuffle? No-one knows (except, possibly, super-SPAD Dominic Cummings).

As regards the taxpayer, the Sector Deal places two large bets, one on immersive technology in the form of a research programme labelled Audience of the Future (£33 million). Another, named the Creative Industries Clusters Programme, focuses on universities as drivers of creative research and development (R&D) and hubs around which creative clusters (there are currently nine) might catalyse partnerships, attract private investment and improve productivity (£39 million, administered by the Arts and Humanities Research Council). These programmes do not lack in ambition, especially given that their terms of reference have explicitly been framed as research for industry, not with or about industry. Just how judiciously these bets have been placed will not be clear for two or three years at least, but some of the early reports are promising. The test, very broadly stated, will be whether either or both these programmes can show evidence of having stimulated measurable growth in new, commercially viable arts-media-design driven enterprise.

At the heart of the Sector Deal, sitting alongside the Clusters Programme, is the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC), a five-year (2018-23) £6 million programme on which considerable hopes have been placed by the sector’s leading figures. In the words of its commissioners (the Arts and Humanities Research Council):

“The Centre “will offer independent analysis on the creative industries for businesses and policy makers, conduct and stimulate research, identify research gaps and co-ordinate data and evidence on the key challenges for the sector.”

This is a tall order by any standards.

In a lecture delivered at Goldsmiths College in December 2019, co-hosted by the College’s Institute for Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship and the PEC, I have tried to position the Sector Deal and the establishment of the PEC within the context of the gestation of public policy over the last two decades, reflecting critically both on what I regard as the undifferentiated official narrative of UK prowess in the creative industries, and on the challenges ahead for cultural industries, as historically understood, within the dynamic emerging ecosystems of what has been labelled ‘Createch’. I draw mainly on perspectives from political economy and investment business but also on experience as a board-level practitioner in the non-commercial (or more accurately non-profit maximising) worlds of arts and culture over some three decades.

The early part of the lecture deals with the classification and terminology of the creative industries since the late 1990s, acknowledging the brilliance of its architects’ achievements qua political marketing, but questioning its continuing utility as a coherent policy construct and asset class and its appeal to cultural producers and practitioners.

The central part of the lecture traces the story behind the announcement of a Sector Deal, including the key episode of the Independent Review of the Creative Industries, by Sir Peter Bazalgette, carried out in 2017. As things stand this ‘deal’ is subject to annual review by the Creative Industries Council, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Separately, HM Treasury is believed to be examining the regime of creative sector tax reliefs introduced between 2007 and 2017. I am concerned about the paucity of evidence on industry performance, behaviour and finances against which to judge the effectiveness of these interventions, three of which (in film, animation and high-end TV) have nonetheless unquestionably been transformational in driving inward investment against the background of a weak pound.

This naturally brings us to the PEC itself. As Hasan Bakhshi wrote in his inauguraI blog as Director:

“There is next to no academic research on the creative industries in essential areas like industrial organisation, productivity, R&D, international competitiveness, spill-overs, content regulation, business models or risk finance.”

Quite so! I therefore conclude my lecture by proposing four research hypotheses with which I believe the PEC should engage over the next three years. These hypotheses relate respectively to:

- The relationship between public and private investment in the creative industries

- The shortage of business and commercial skills in the sector

- The threat (as I see it) to cultural industries, cultural labour and cultural enterprises posed by ‘Createch’ agendas

- And finally the old chestnut of ‘access to finance’ (or access to investible propositions as fund managers prefer to describe it).

I hope that the PEC will be able to help us make progress in these areas of knowledge and understanding.

Photo by Daniele Levis Pelusi

The PEC’s blog provides a platform for independent, evidence-based views. All blogs are published to further debate, and may be polemical. The views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent views of the PEC or its partner organisations.

Related Blogs

Taking stock of the Creative Industries Sector Plan

We summarise some of the key sector-wide announcements from the Creative Industries Sector Plan.

Why higher education matters to the arts, culture and heritage sectors

Professor Dave O’Brien, Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries at University of Manches…

What does the 2025 Spending Review mean for the creative industries?

A read out from Creative PEC Bernard Hay and Emily Hopkins On Wednesday 11th June the UK Government …

Bridging the Imagination Deficit

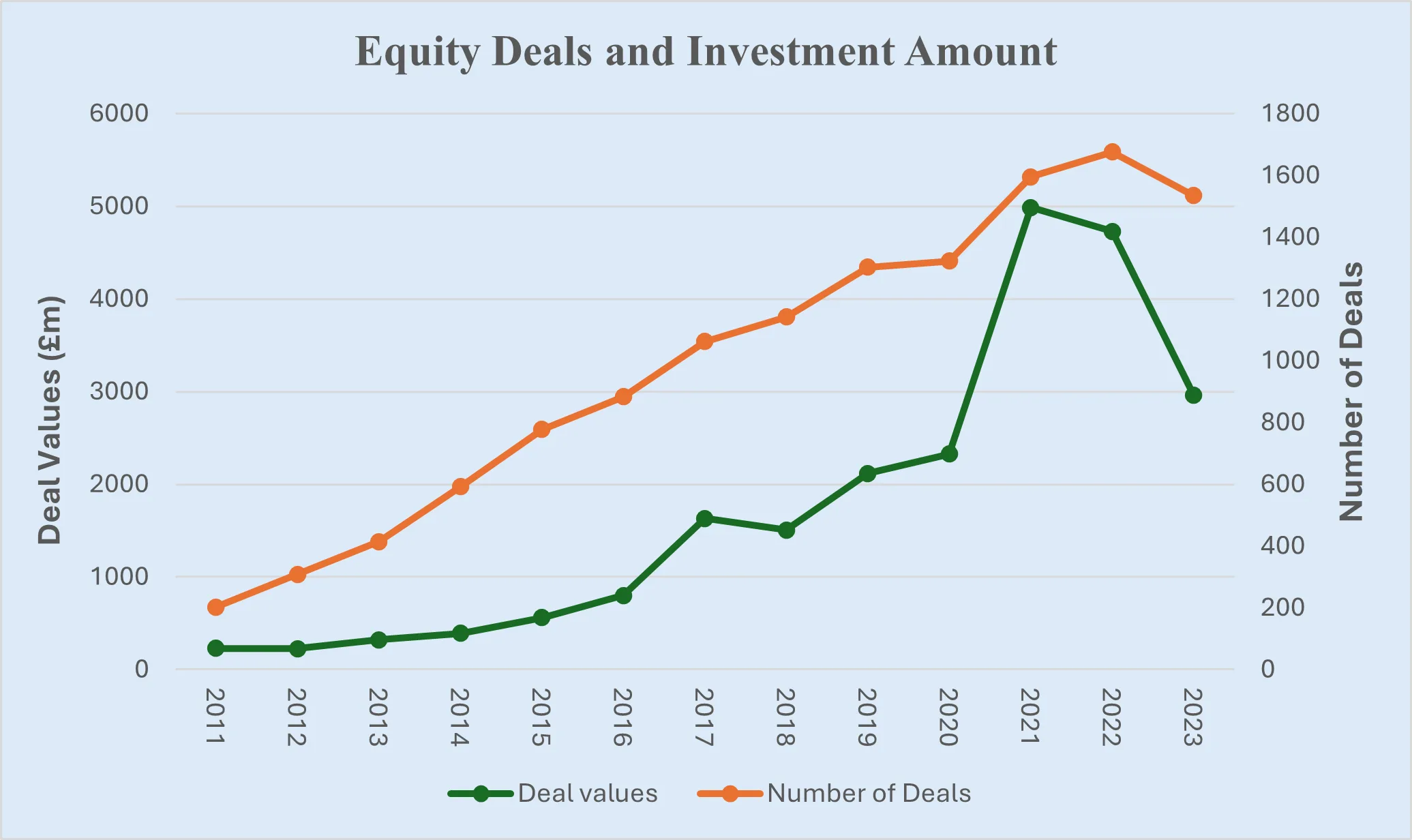

The Equity Gap in Britain’s Creative Industries[1]. by Professor Nick Wilson The creative industries…

Why accredited qualifications matter in journalism

Journalism occupations are included on the DCMS’s list of Creative Occupations and, numbering around…

All Together Now?

Co-location of the Creative Industries with Other Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Dr Josh Siepe…

The Mahakumbh Mela, India, 2025

The festival economy: A Priceless Moment in Time Worth GBP 280 Billion in Trade Jairaj Mashru looks …

Class inequalities in film funding

Professor Dave O’Brien, University of Manchester, Dr Peter Campbell, University of Liverpool and Dr …

Creative self-employed workforce in England and Wales

Dr Ruoxi Wang, University of Sheffield and Bernard Hay, Head of Policy at Creative PEC Self-employed…

What just happened to funding for culture in Scotland?

First the facts: Creative Scotland announced the outcome of its new Multi-Year Funding Programme on …

Copyright and AI – a new AI Intellectual Property Right for composers, authors and artists

Background The new technology landscape emerging from the super rapid progress in developing AI, Gen…