I was recently reminded of a ‘think piece’ that I wrote in 2005, for the then Department of Trade and Industry (now BEIS), on the role of design in business performance. In it, I quoted approvingly Alan Topalian, a long-time design advocate, as stating that “All organizations – bar none – use design. No product, service or process can be introduced without design”. I thought that was true at the time, and still I think it is true today. On this at least, I am in good company. The late Herbert Simon wrote “everyone designs who devises course of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones”. This is not to say, of course, that all organisations use design well, or that every organisation uses the skills and insights of trained designers or professional design consultants.

One of the paradoxes of design is that while it is everywhere, it is often unrecognised. In 2016 the European Commission sponsored a survey which asked firms about, among other things, their use of design.

Among the 13,000 firms responding, only one in eight (12%) considered that design was a central element in their strategy, and about one in five (18%) considered it to be an integral, but not a central element of their development work. Another one in six (17%) stated that they used design, but not systematically. Combined, this makes is less than half the firms. Among the other half, a small number of respondents (2%) did not know about their company’s use of design, while one in seven (14%) recognised that they used design, but only as a last finish to enhance the appearance or attractiveness of their final product. 37%, meanwhile, declared that ‘design is not used in this company’.

Design has attracted relatively little, but now growing, interest from economists and scholars of innovation. My own interest dates back to my PhD, undertaken in the early to mid-1990s, for which I undertook a study of award winning innovations. I naively combined into a single dataset the innovations that had won the Queens Award for Technological Achievement with the new products that had won the British Design Award. They were not the same! As one respondent to my survey pointed out: “Your questionnaire often refers to technological developments, R&D and innovation, and whilst this is very frequently applied to a new product, it is distinct from ‘good design’. Do you consider the British Design Awards for design or technology?”

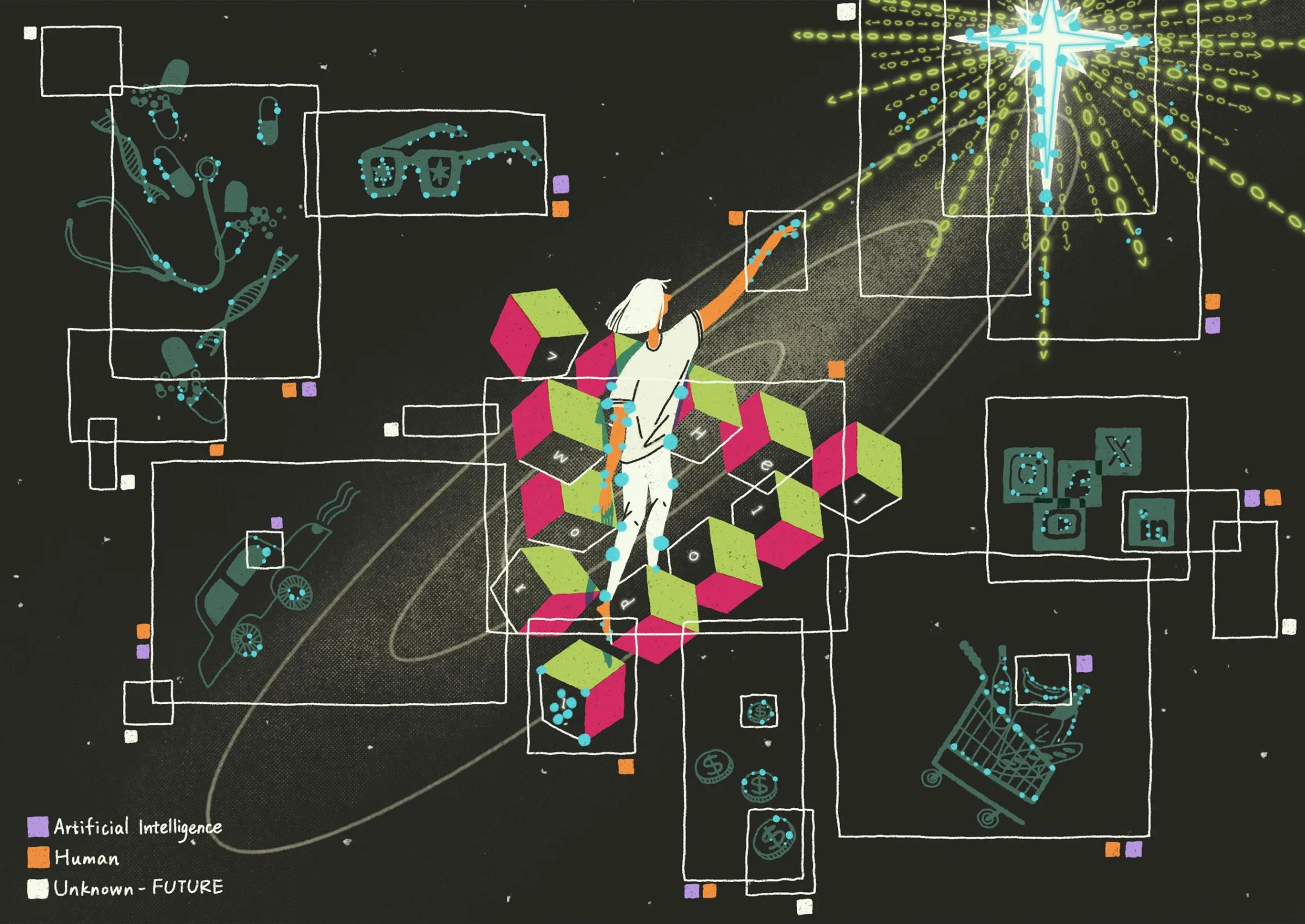

Much more recently I read “the Creative Economy” speech given at the Glasgow School of Art by Andy Haldane, the Chief Economist at the Bank of England. Haldane highlights that imagination and creativity are what separates humans from other animals; they are “wellsprings of improvements in economies and societies”. For me, imagination and creativity are central to design (although also not exclusive to design!). Design involves the human ability to separate imagined situations or futures from existing realities; to generate multiple possible alternatives; to conceptualise better situations; to think ‘what might be?’ Imagining without action is, as Haldane observes, day-dreaming. What sets humans apart is our ability to generate our imagined futures; to create alternatives in our individual and collective minds, and then select among those, deciding which to ‘make real’. This, for me, is the essence of design.

One reason why design is often unrecognised is there is widespread confusion as to what it is. As the results of the European Commission survey reported earlier indicate, many people think design is (only) about styling. The contrast with R&D is illuminating. The standard approach to identifying and measuring R&D was first developed in the early 1960s. The story goes that an international group of National Experts on Science and Technology Indicators (NESTI) met at the Villa Falconieri in Frascati, Italy to discuss defining research and experimental development. A background document had been prepared by Chris Freeman, later the founding director of the highly influential Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) at the University of Sussex, where, incidentally, some thirty years later I did my PhD. Discussions, apparently, did not go well; there was no agreement. The group then broke for dinner, consumed substantial quantities of wine and rapidly came to agreement. Some proposed that ‘design’ be included alongside research and experimental development, making ‘RDD – Research, Design and Experimental Development’ rather than R&D. Unfortunately insufficient wine, or perhaps grappa, had been consumed to agree a definition of design, so it remained in the ‘too difficult to define’ box.

The “Frascati Manual” which defines R&D is now in its seventh edition (published 2015). It runs to 402 pages, which demonstrating that R&D is hardly easy to define and measure. Design is partially included and partially excluded from R&D; the Manual recognises that they are difficult to separate. Certainly some design is accepted as qualifying as experimental development. It is not, however, explicitly identified and therefore remains hidden. And, unlike investments in R&D, there are no official statistics on design and design investments. The Design Council has used existing statistics to estimate that in 2016 the design economy contributed £85 billion in gross value added to the UK economy, directly employed 1.7 million people, and grew by 52% between 2009 and 2016.

What has this to do with the ‘creative industries’? Well, the two largest of the Design Council’s design-intensive industries are also ‘creative industries’, as defined by the DCMS. These are architectural activities and specialist design activities. According to the Office for National Statistics, the architecture industry directly employs around 80,000 people and generates around £6.3bn in value added. Specialist design activities, meanwhile, employ around 55,000 people and generate around £3.8bn in value added.

One might argue that the architecture industry in the UK is relatively strong, and that the market for architecture functions reasonably well. Among other economic indicators of it strength are its exports valued at half a billion pounds, compared with imports of around 40 million. The design industry, on the other hand, is arguably under-performing. In particular, I believe there is a huge opportunity to apply design to services, and experiences, both through in-house design activities and through the employment of design consultants. And notably some UK consultancies, including Engine Service Design, Live|Work and ThinkPublic pioneered the application of design to services from the early 2000s.

Services are a messy category, but the UK economy is around 85% services. This provides an enormous space which is ripe for the application of ‘design thinking’, and more specifically service design. Services do very little R&D; they also engage in little explicit design. There is huge potential here.

In my role at the PEC’s research director I will be overseeing the full breadth of our research activities. Much of my own personal research and policy interest will be in design, and the design-industries. If you share this interest, please do get in touch.

For anyone unfamiliar with design, I suggest that a great place to start is with “Design: A very short introduction” by the late John Heskett. An accessible introduction to innovation by design is provided by Tom Kelley’s “The Art of Innovation”. Kelley is a partner at IDEO, one of the world’s leading design consultancies. Tim Brown is IDEO’s Chairman and CEO, and the author of “Change by Design”, which provides as introduction to ‘design thinking’. If you want a short introduction then Brown’s Harvard Business Review articles is a good place to start.

There is of course a huge number of academic works on design. Where to start? Nigel’s Cross (“Designerly Ways of Knowing”) and Bryan Lawson (“How designers think”) provide great insight into design cognition and attitude. I also enjoy and recommend histories of design, including books by Jonathan Woodham (including “Twentieth Century Design”) and Jeffrey Meikle’s (“Twentieth Century Limited”).

Suggested reading

Brown, T. (2009) Change by Design, New York: Harper Collins

Brown, T. (2008) Design Thinking, Harvard Business Review, June, pp.84-92

Cross, N. (1982) Designerly Ways of Knowing, Design Studies, 3(4), pp.221-227

Design Council. (2018) The Design Economy 2018. Available at: https://www.designcouncil.org.uk/resources/report/design-economy-2018 [ Accessed March 2019)

Haldane, A. (2018) Creative Economy, The Inaugural Glasgow School of Art Creative Engagement Lecture, available at: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2019/the-creative-economy-speech-by-andy-haldane.pdf?la=en&hash=4A3B2C4C6F810E5F16BE72A6990C37C7C59CF4BA [Accessed March 2019]

Heskett, J. (2005) Design: A very short introduction, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Kelley, T. (2002) The Art of Innovation, London: HarperCollinsBusiness

Lawson, B. (2005) How Designers Think: The Design Process Demystified, 4th Ed, Oxford: Routledge

Meikle, J. (2001) Twentieth Century Limited: Industrial Design in America 1925-1939, 2nd Ed, Philadelphia: Temple University Press

OECD, (2015) Frascati Manual, available at: http://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/frascati-manual.htm [Accessed March 2019]

Simon, H. (1996) Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd Ed, London: MIT Press

TNS Political and Social. (2016) Flash Eurobarometer 433: Innobarometer 2016 – EU business innovation trends. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/ResultDoc/download/DocumentKy/73870 [Accessed March 2019]

Woodham, J. (1997) Twentieth Century Design, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Related Blogs

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Take our Audience Survey

Take our quick survey and you might win a National Art Pass.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…

Reflections from Creative Industries 2025: The Road to Sustainability

How can the creative industries drive meaningful environmental sustainability?