The beginning of this new decade, the 2020s, was marked by irreversible disruptions. For the first time in a century, the world population faced a pandemic that spread globally, affecting human beings both physically and mentally. Worldwide, there have been 32 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, with over one million deaths during the first nine months of this year. Society was already undergoing a deep process of transformation on all fronts, but the magnitude and wide-reaching impact of this unexpected pandemic took humanity by surprise.

In the early months of 2020, general debate was focused on the fragility of democracy, climate change and biodiversity, inequality and inclusion, gender and sex, social media and fake news, virtual payments and crypto currencies, artificial intelligence and blockchain. Science, knowledge and technology were advancing at a fast rate in all fields including genetics and biotechnology. Nevertheless, healthcare was not a top priority for public investment or national budgets. Yet, with the eruption of the pandemic, priorities had to be immediately revisited. A human-centred and inclusive approach became imperative in every corner of the planet.

Lockdown measures and social isolation deprived individuals of free movement, restricting social gatherings and citizen mobility. The home office dismantled solid organisational structures of daily work conviviality, and the closure of schools prevented children from accessing formal in-person education as well as creating a childcare crisis for working parents. Once crowded urban centres became empty with no shopping, restaurants or city life. Cultural festivities and spaces such as theatres, cinemas, and museums had their activities suspended, leaving artists, cultural producers and creative professionals, as well as street vendors, out of jobs. Parks and sports centres became inactive and international tourism halted.

Conversely, family life became the heart of social order. Parents that were extremely busy with their jobs had to juggle work and the education of their children. Solidarity has been manifested in donations and collective assistance by civil society. Artists, cultural and creative professionals were challenged to work even harder at home to find niches in the virtual domain. Society, now confined, had to rediscover its ethical values, principles and priorities. Wellbeing and happiness became the essence of achievable goals.

Free time and leisure revisited

Paradoxically, this shift in human behaviour brought us back to a theory of economics that emerged a century ago (Ruskin, 1900) “There is no wealth but life”. In this new-old context, free time, leisure, wellbeing and culture are closely associated. Usually, we use our free time to carry out activities that are not directly related to work, duties or domestic occupations. Leisure, however, is a subjective concept which varies depending on the society to which we belong. It is connected with our participation in cultural life, reflecting the values and characteristics of a nation. Thus, it can be considered a human right according to the UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and in particular the 1967 International Convention on the Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

There are different views about the definition of leisure but there is convergence around three distinctions: leisure as time; leisure as activity; and leisure as a state of mind. Firstly, it is defined as the moments free of obligations meaning the constructive use of available time. Leisure as a variety of activities includes the practice of sports or actions related to intellectual and human development like reading, painting and gardening, and those can be leisure for ones and work for others. Understanding leisure as a state of mind is complex since it depends on individual perceptions about concepts such as freedom, motivation and competency. Certain skills can be considered leisure depending on the degree of satisfaction, emotion or happiness it causes. Yet, the most important is the possibility of free will.

Moments of leisure are essential in all phases of our life. During childhood and adolescence most of our time is devoted to study and sports while during adulthood our time is mostly consumed with work and family. Indeed, it is at senior age that people may have extra free time to enjoy cultural events, leisure and tourism. Globally people are living longer and a new age structure is taking shape: the young senior (65-74 years), the middle senior (75-84 years) and the older senior as from 85 years old. According to the United Nations in 2018, for the first time in history, people aged 65 years or over outnumbered children under age five.

Wellbeing and spirituality in contemporary times

During the pandemic, we have reflected more on the importance of wellbeing and spirituality. It is undeniable that constraints brought about by lockdown measures and social distancing offered us more free time but very limited leisure options. Nevertheless, we gained additional time to be closer to loved ones. Enjoying family life, including eating and even cooking together became a shared pleasure and a new leisure style.

Global pandemics affect our collective mental health. Given the prevailing health and economic insecurity, the focus has been on wellbeing, strengthening friendships, expanding our social networks, practicing solidarity, improving self esteem, as well as reflecting on spirituality and religion. Suddenly the exuberant society of 2020 is afraid of the unknown virus and its long term harmful economic, social and cultural consequences on daily life.

In this moment of tension, people are emotionally fragile. Individuals are suffering losses that will persist long after the pandemic will be over. Some feel stressed or depressed while others react by searching for relief in exercising, relaxation, meditation, yoga, or mindfulness training. In Brazil, at the International Day of Peace on 21st September, the festival Virada Zen celebrated the culture of peace with a global and simultaneous meditation, with the participation of over 200 spiritual leaders and teachers offering an experience of connection and wellbeing through practices such as mindfulness, culture of peace and yoga as well as diversity and human development.

Inspirational talks, given to like minded groups, have been helpful in reconnecting people dealing with an uncertain future. Individuals are finding new ways to overcome solitude and boost mental resilience. Social engagement and advocacy for health causes are used for promoting social change. Thus, besides upgrading healthcare systems and putting in place special measures for accelerating economic recovery and cultural events, more governmental support will be needed to improve mental wellbeing and raise the overall level of satisfaction and happiness of citizens in the post-crisis.

Culture and e-learning in the virtual era

In a short period of time, many went from an exciting social and cultural lifestyle to a simple life. Due to open-air limitations, free time activities had to be less physically intensive (no bike, tennis, jogging etc), and more creative oriented such as designing, painting and writing. Much time has also been spent watching TV series, surfing the internet, viewing live music concerts, video gaming, attending video conferences as well as socialising in virtual chats.

A recent study carried out by AudienceNet for the PEC and Intellectual Property Office in the UK to track digital cultural consumption during the first UK lockdown as a result of the pandemic, indicates that the median time spent daily watching TV was four hours, while listening to music, watching films and playing video games each day were three hours respectively. Understanding human behaviour, particularly the habits of younger people, can help to indicate new cultural trends and consolidate social cohesion in post-pandemic times. Furthermore, policymakers could consider engaging cultural institutions and employing artists and creatives to help facilitate a collective healing process and kickstart recovery .

It is widely recognised that the arts, culture and creative sectors were hit hard by the pandemic. Whilst digital cultural and creative products for home consumption were in high demand, other tangible creative goods like arts, crafts, fashion and design products sharply contracted. Many artists and creatives had no option than to experiment on work in digital spaces.

Despite the fact that 4.5 billion people (60% of the global population) use the internet, the availability of affordable broadband access is a pre-condition to benefit from the opportunities provided by digital tools. This applies to both producers and consumers of cultural and creative digital content. At present videos account for 80-90% of global digital data circulation, but at the same time Latin America, the Middle East and Africa together represent only around 10% of world data traffic. This evidence points to digital asymmetries that are being aggravated. Creativity alone is not enough to transform ideas into marketable creative products or services if digital tools and infrastructure are not available.

The pandemic also had a significant impact on education and learning. Re-thinking education was already a topic on the agenda of many countries in order to respond to the realities of the future jobs market. Besides the need to adapt methodology and pedagogical practices, many believe it is necessary to bring an interdisciplinary and applied approach to curricula with focus on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), preferably also integrating arts (STEAM). In any case, the education system has been forced to quickly adjust to remote learning. Globally over 1.2 billion children are out of the classroom in 186 countries. In Latin America, schools are closed and around 154 million children between the ages of 5 and 18 are at home instead of in class. Moreover, access to school related material is distributed in an unbalanced manner; wealthier students have access to internet and home schooling while the poorer have not. Young people are losing months of learning and this will have long-lasting effects. The loss of future human capital is enormous.

On the positive side, continuous e-learning has become a trend and a necessity. Innovation and digital adaption gave rise to a wide range of online courses. Millions of learners are upgrading their knowledge and skills in different domains through distance learning, whether through language and music apps, video conferences or software learning. Some are free, others have to be paid for, with or without certification, and at different levels, but what is absolutely transformative is that access to knowledge has the potential to become more democratic. Independently of age or field of interest, learners from different parts of the world can have access to prestigious universities or practical training. E-learning, where teaching is undertaken remotely and on digital platforms, already existed but demand has sharply increased during pandemic and this might be a point of no return.

Over these critical nine months, there are growing signs that the 2020s will face a new set of challenges and life will not be back as usual. The future will be very different when compared to the recent past. Hope and fear are likely to co-exist for a certain time. There are new values, new lifestyles, new social behaviour, new consumption standards, and new ways of working and studying. The pandemic has imposed a deep ethical and philosophical reassessment on society. This turning point is leading to a deep socio-economic renovation and hopefully to a more inclusive and sustainable society.

Photo taken by Edna dos Santos-Duisenberg

This is a follow up piece to our COVID-19 blog series from our International Council.

The PEC’s blog provides a platform for independent, evidence-based views. All blogs are published to further debate, and may be polemical. The views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent views of the PEC or its partner organisations.

Related Blogs

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

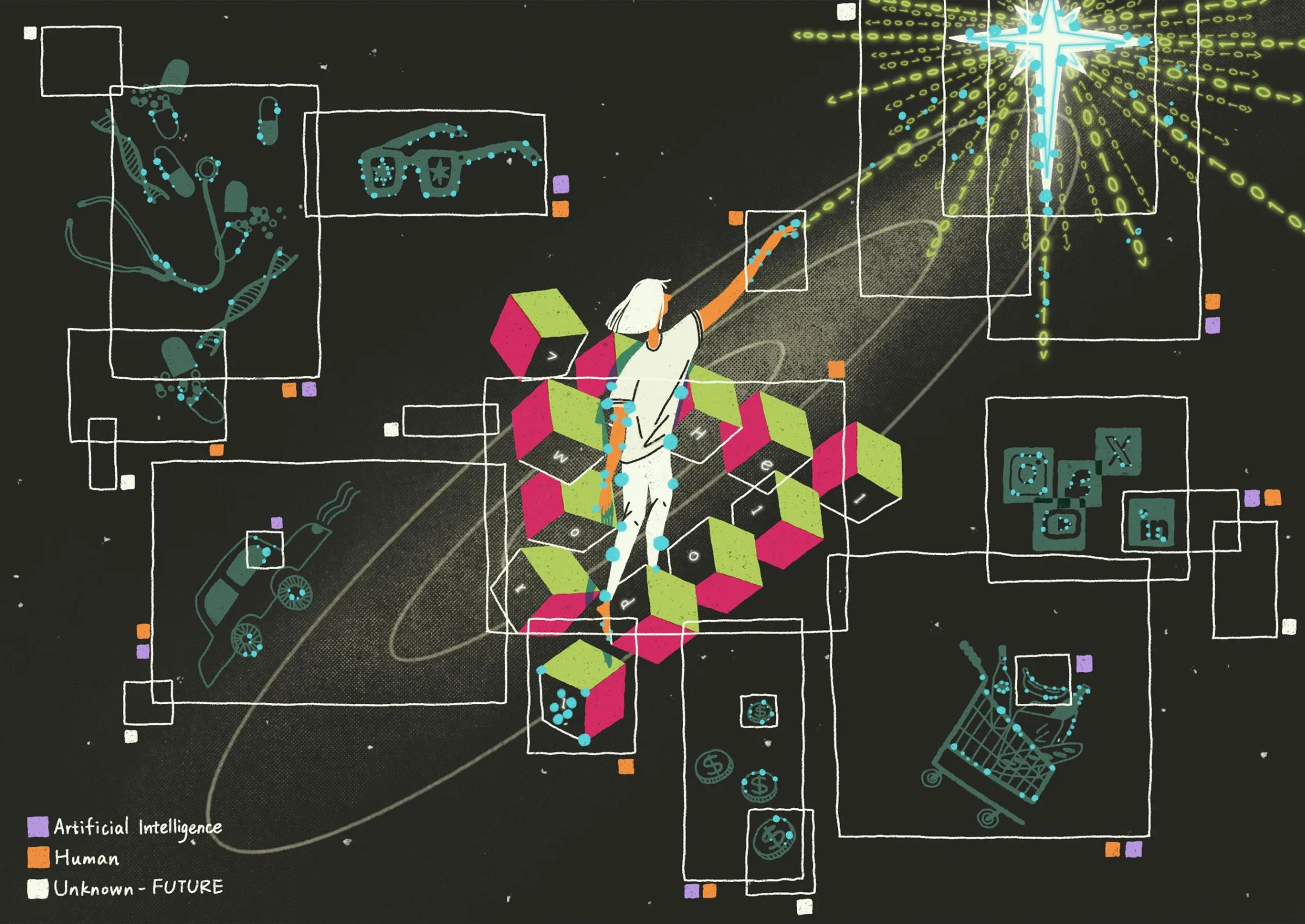

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…