There is an incoherence at the heart of government policy. While Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries is calling for more social diversity in the arts, the Department for Education is pursuing policies that systemically undermine inclusivity in the creative talent pipeline. The divergent approach to arts education in the state and private sector contributes to the unequal access seen in industry.

With the Government’s new Sector Vision for the Creative Industries expected in a matter of weeks, Dorries has signaled she wants the sector to be more inclusive, saying “We have to do better at making sure that people from deprived backgrounds instinctively feel that the creative industries are for them, too.”

In England approximately 93% of the population attend state-funded schools compared with 7% educated in the private sector. Yet recent research from the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, found that people from more privileged backgrounds are twice as likely to be employed in the cultural sector. In ‘Music, Performing and visual arts’ just 22% are from more working-class backgrounds compared with 60% from more ‘privileged’ backgrounds. Similarly, The Sutton Trust found that 38% of the wealthiest individuals in TV, film and music and 44% of newspaper columnists attended private schools.

The root of the perceived and actual elitism of the cultural sector, which Dorries says she wants to tackle, lies partly in our fractured education system, and deliberate policies of undermining the arts in state schools.

My new research from the Centre for Culture and Media Policy Studies at Warwick University, finds that private schools are investing substantially in arts and culture provision and indeed schools such as Eton make a virtue of “providing a broadly-based education designed to enable all boys to discover their strengths, and to make the most of their talents within Eton and beyond”. Of the twenty private schools we looked at, they had between them 33 theatre spaces available for teaching and performances, with facilities often exceeding those of even professional theatres . All twenty had dedicated provision for concert performances, all had fine art studios, and all had specialist provision ranging from photography, sculpture, ceramics, textiles, digital media and more. Ninety per-cent had dedicated rehearsal and music practice rooms (with some having as many as 15 rehearsal spaces at their disposal).

Perhaps even more significantly the facilities are supported by industry professionals and programmes such as ‘Artist or Filmmaker in Residence’. Attracted by the higher salaries the private sector is able to offer, the teaching staff as well as the theatre managers, technicians and administrators, boast CVs with extensive industry credentials including for example recent experience at the National Theatre, the West End and with TV and film credits. These industry links provide highly-valuable contacts, social capital and up-to-date specialist teaching.

While the private sector recognises the economic and social benefit of investing in their cultural facilities, the state sector has seen a significant reduction in provision for arts and culture over the last twenty years. This is against a backdrop of a mental health crisis among young people, with a survey from the charity BeatFreeks finding 93% of 16-18 year olds say studying an arts subject – which encourages self-expression, collaboration and empathy – had impacted positively on their well-being.

Two key policy actions have culminated in the marginalisation of the arts in state education; the introduction of The English Baccalaureate (EBacc) and the funding cuts as part of austerity policy.

Since the late 1990s there has been an increasing focus on ‘core’ subjects in state education. This evolved into a prioritisation of Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths ‘STEM’, and then in 2011 the EBacc was introduced. It excludes all arts-based subjects and controversially was adopted without robust scrutiny or parliamentary consultation.

Alongside the introduction of the EBacc English schools have seen a significant decrease in funding. In 2020 the Institute for Fiscal Studies, reported a 9% drop per student over the preceding decade. Schools have little autonomy in their educational provision and have been forced to divert resources towards the subjects on which they are measured, namely those included within the EBacc.

The result, as evidenced in the government’s ‘Taking Part Survey’ , is a drop of 47% in participation in theatre and drama subjects and a drop of 36% for music over the last 10 years, with children from the poorest backgrounds most likely to experience the loss.

The divergent approaches to arts and cultural education pursued by the private and state education sector, provide some insight into the startling inequality we see in the creative industries. While Nadine Dorries puts the onus on arts organisations to be more accessible, as indeed they should be, any action is likely to be ineffective, if 93% of the population are systemically discouraged from thinking that the worlds of theatre, television, publishing or music are meant for them.

____________________________

This opinion piece is a guest blog for the Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre and is based on new research ‘Creativity and the curriculum: educational apartheid in the 21st Century England, a European outlier?’ by Heidi Ashton and David Ashton.

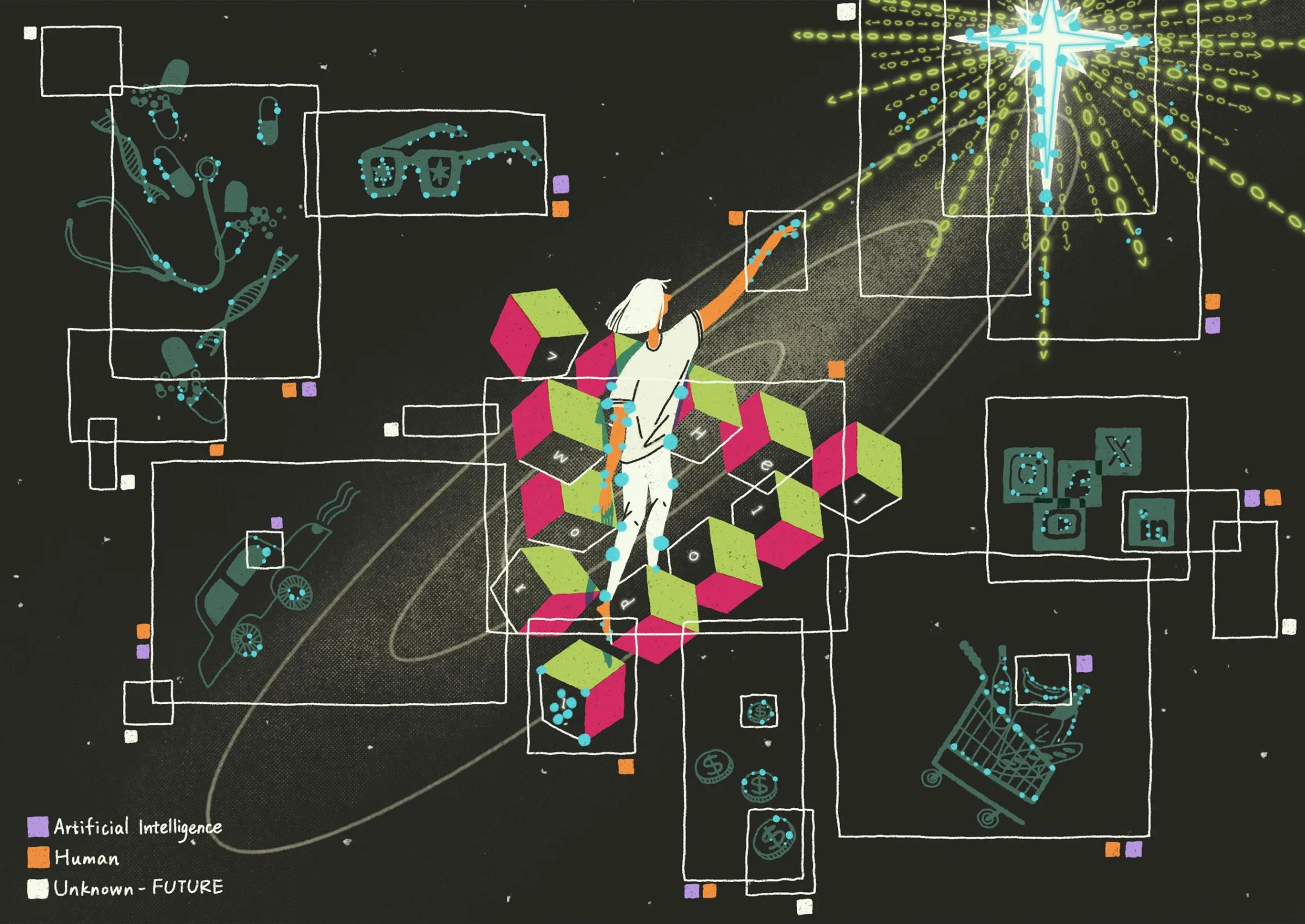

Image credit danielwatsondesign.co.uk

Related Blogs

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…