When thinking about why we publicly fund the arts, we can point to their multifaceted benefits. Not only do the arts contribute directly to the economy, but they can be important for health and wellbeing; not only can they make people love the place they live in but they also help to shape the global view of the UK.

Of course, not all investments in the arts do all these things – nor should we want them to. Some investments are about pushing the frontiers of forms or technologies, whilst others may be aimed at giving children their first taste of a museum, sparking lifelong curiosity. The same theatre may produce one show which traverses the world, and another created by and for a specific local community. This web of public benefits is explored in detail in the 200-odd-page AHRC Cultural Value Project report (amongst others), as well as being an ongoing subject of discussion for the Centre for Cultural Value.

These myriad benefits link to many policymakers’ objectives for public money, whether that is funding to support innovation, unlock health benefits or make us proud of the places we live in. That is why policymakers at all levels – from those in international bodies (like UNESCO), to national governments, to local policymakers – have historically invested in the arts.

It therefore should be no surprise that public funding for the arts in England comes from many different sources. Some of these are aimed specifically at the sector and some – like the Levelling-Up funds, or the NHS budget – may not aim to fund the arts in particular but invest in them when they can help them to achieve their objectives.

Today the Creative PEC publishes a data set, collected from public data sources, which hopes to start a discussion about how investment through the largest of the pots of public investment directly aimed at funding the arts has changed since 2009/10. The dataset includes most of the available funds in England although, as we will later discuss, there are still data points we would like to add and these numbers should not be taken to represent the totality of public investment in the arts. We report these figures in both nominal and real terms (meaning in terms of the actual amount of money given, and what that amount means once you take the impact of inflation into account).

We seek to use this data set to start a conversation about whether the current funding pots are fit for purpose in supporting the delivery of the impacts we want the publicly funded arts sector to have.

To help future research, we link to all of the original sources hoping that researchers, policymakers and industry representatives from all backgrounds find this a useful starting point for their long-term thinking on arts policy. We welcome feedback from all three of these groups.

Initial analysis

The most obvious story hidden in this dataset is perhaps the one about the decline in local government funding.

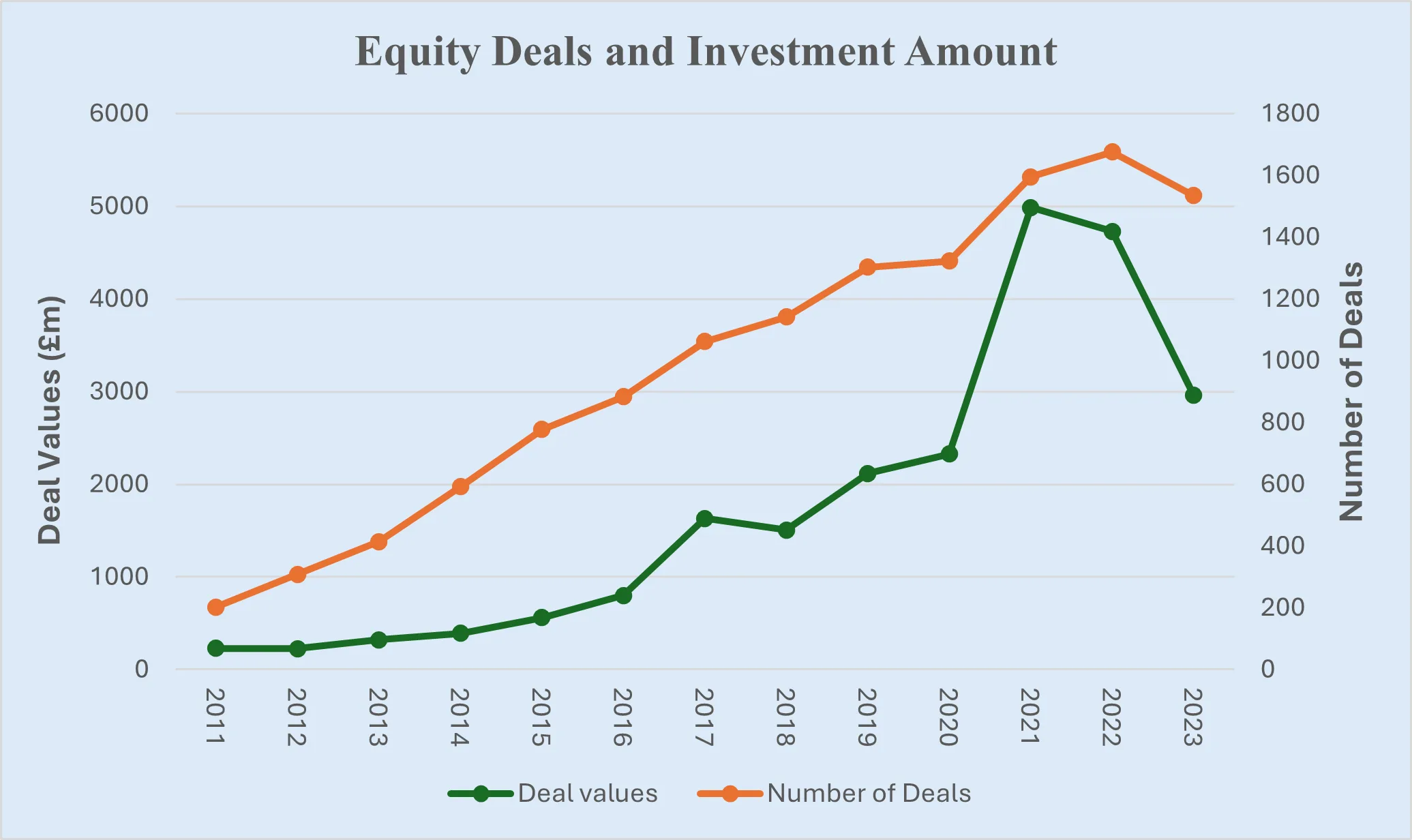

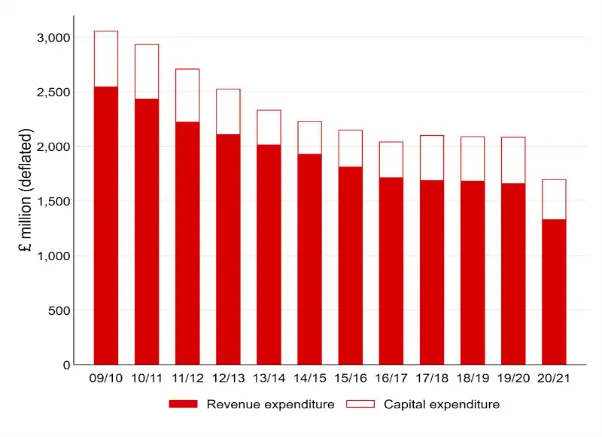

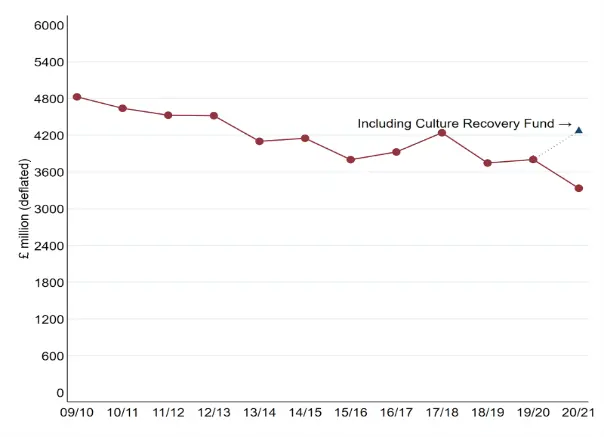

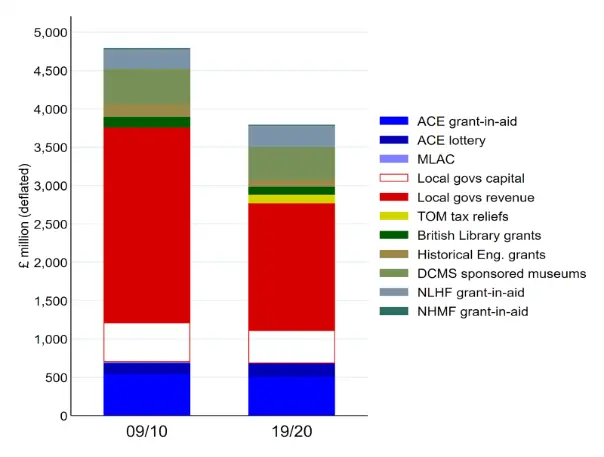

The investment in the arts through Local Authorities in capital and revenue expenditure in the arts in England has fallen by more than 30% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2019/20 in response to an overall decline in local government budgets over this period (Figure 1). Much of this comes from a significant drop in funding to libraries, although excluding libraries we still find a 15% drop in real terms from 2009/10 to 2019/20.

As the largest public funder of the arts in England, this obviously has severe implications for the funding of the sector in general – but it also has implications for the type of art we should expect to be funded by the overall public settlement.

Local Government funding for the arts has always helped to support local projects. Whilst it can (and does) bring in significant leverage from other public sources like Arts Council England, as well as private sources, and can aim to achieve all sorts of ambitious outcomes including boosting British soft power and improving health outcomes, its core benefits have historically aligned closely with the kind recently set out in the Government’s Levelling Up strategy for example improving civic pride, levels of investment in and resilience of the local economy, or raising levels of tourism.

However, with changing overall budgets across Government impacting the Local Government settlement, this steady investment in making areas more attractive, fostering local communities, developing education programmes, and improving local wellbeing has been eroded. Whilst other investments in local arts have emerged – namely the UK City of Culture scheme, the Government’s Towns Fund, Levelling Up Fund and Community Ownership Fund, Arts Council England’s “priority places”, and Historic England’s Heritage Action Zones and High Street Heritage Action Zones programmes – these are most often competitive processes which will invest in specific areas for set periods of time and do not replace that long term investment in key local infrastructure. In this context, it is worth pointing out that the most significant local government funding support is revenue funding, and it’s the decline in this that has been most significant. The other Government funds listed here, be these place-based or not, are more likely to be capital funding (this is also the case for the Cultural Development Fund, which is included in the Arts Council England funding in our data series) so they cannot directly replace the funding which has disappeared. We suggest that the type of art that can and will be funded should this trend continue is fundamentally different, despite the shared focus on the local.

So, in truth, this data set suggests a need to take a step back, take stock and ask: what do we want the arts to deliver? And where should funding come from to allow it to best deliver that impact? In the case of Local Government funding, it may be that we need to be realistic about the likelihood of it returning to its early-2000s levels, and if that is the case perhaps a conversation is needed looking at other devolution and levelling-up funds and considering how we can make sure they provide sustainable investment for local infrastructure and the communities it serves.

Other stories are hidden in the data – whilst the real-term value from Grant-in-aid has slightly fallen, new tax incentives have been introduced. This could suggest the way in which policymakers want to support the arts has shifted (although no single fund should be taken as a direct replacement for another). And noting what is missing raises other questions. There is no fund listed here which has a clear ‘soft power’ remit. Whilst the British Council is clearly the major player in this field, it would be remiss not to note the huge soft power importance of cultural organisations in major tourist destinations within the UK (soft power can be defined as a country’s cultural and economic influence to persuade other countries to do something, rather than the use of military power). Once again, we suggest that a lack of clarity on the objectives of arts funding leads to confused conversations about what should and shouldn’t be supported.

We recognise this data set is far from complete. There are other pots of money not listed here, which include funds for the visitor economy, and pan-economy measures, as well as money from trusts and foundations, commercial income and philanthropists. Some pots are open to the whole UK; others to England alone. We hope, in future, to be able to add some additional cultural funds as further data becomes available. And of course, there are funds which have been introduced – e.g. the Cultural Investment Fund – which haven’t given out funds over our time series but will feature in future years (more information available from Arts Council England and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

In addition, speaking to those in the sector, we believe that over time the public money that is invested in the public arts (particularly that given as part of Grant-in-aid) has been increasingly likely to come with specific outcomes tied to it. This means that under the surface, the dynamics are even more complicated than they first appear, with the ambitions of the individual pots increasingly impacted by changing Government priorities. Further data and research on this trend is sorely needed.

Conclusion and next steps

In bringing together these data points we were aware that the biggest question we were going to be asked is how much overall public investment has changed over time. In short, we find that across the pots we looked at real terms investment has decreased by circa 21% from 2009/10 to 2019/20 (Figure 2). The Culture Recovery Fund (CRF) mitigated this drop, with the corresponding % reduction from 2009/10 to 2020/21 being circa 12% (31% if not considering CRF).

But we ask readers not to focus on any specific number alone. With UKRI investment in innovation, and the Shared Prosperity Fund, the Government is putting money into significant investment pots which are seeking to have some of the impacts the arts are good at producing. But the sector, with policymakers and researchers, need to seek clarity and a common understanding of the type of investment they most need, and how that can be delivered to ensure that the full funding package for the arts protects the infrastructure that it needs to survive, while also continuing to have the range of impacts that most benefit the nation. In short, we expect that the arts in England are unlikely to again be funded in the same way they were in 2008/2009, instead they need now to ask for a new deal.

Note: Annual spend in the public arts is obtained from the following funds: 1) Arts Council England grant-in-aid, 2) Arts Council England National Lottery grants, 3) British Library grant-in-aid, 4) Historic England, 5) DCMS directly sponsored museums and galleries, 6) National Lottery Heritage Fund, 7) National Lottery Memorial Fund, 8) Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, 9) Local authority revenue expenditure (including archives, arts support, heritage, libraries, museums and galleries, and theatre and entertainment), 10) Local authority capital expenditure (including culture and heritage, and libraries), 11) Theatre, Orchestras and Museums (TOM) tax reliefs, 12) Cultural Recovery Fund channelled via Arts Council England and National Memorial Heritage Fund

Note: TOM tax reliefs were not in place in 2009/10 and MLAC funding was no longer in place from 2013/14.

Whilst any mistakes in this blog and data set are our own, there are many people to whom we owe a debt of gratitude in helping us to bring this piece of work to completion. These include colleagues at Arts Council England, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and the Arts and Humanities Research Council, as well as critical friends from across the research and arts sectors, including Creative PEC colleagues.

Hero image by James Genchi on Unsplash

Related Blogs

Taking stock of the Creative Industries Sector Plan

We summarise some of the key sector-wide announcements from the Creative Industries Sector Plan.

Why higher education matters to the arts, culture and heritage sectors

Professor Dave O’Brien, Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries at University of Manches…

What does the 2025 Spending Review mean for the creative industries?

A read out from Creative PEC Bernard Hay and Emily Hopkins On Wednesday 11th June the UK Government …

Bridging the Imagination Deficit

The Equity Gap in Britain’s Creative Industries[1]. by Professor Nick Wilson The creative industries…

Why accredited qualifications matter in journalism

Journalism occupations are included on the DCMS’s list of Creative Occupations and, numbering around…

All Together Now?

Co-location of the Creative Industries with Other Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Dr Josh Siepe…

The Mahakumbh Mela, India, 2025

The festival economy: A Priceless Moment in Time Worth GBP 280 Billion in Trade Jairaj Mashru looks …

Class inequalities in film funding

Professor Dave O’Brien, University of Manchester, Dr Peter Campbell, University of Liverpool and Dr …

Creative self-employed workforce in England and Wales

Dr Ruoxi Wang, University of Sheffield and Bernard Hay, Head of Policy at Creative PEC Self-employed…

What just happened to funding for culture in Scotland?

First the facts: Creative Scotland announced the outcome of its new Multi-Year Funding Programme on …

Copyright and AI – a new AI Intellectual Property Right for composers, authors and artists

Background The new technology landscape emerging from the super rapid progress in developing AI, Gen…