This blog is based on the discussion paper Crypto Art and Questions of Value, a guide for anyone interested in NFTs, blockchain, crypto art, and the impact of these new technologies on artists and cultural institutions.

The birth of NFTs

In March 2021, the auction house Christie’s sold a digital artwork – Everydays: The First 1000 Days – by the artist Beeple for an unprecedented $69 million. The sale caught the public’s attention and received widespread coverage. Many responses were highly critical, some attacking the aesthetic quality of the artwork, with Sebastian Smee in the Washington Post dismissing it as ‘a marketable digital product by a graphic designer’, while Jason Farago writing for the New York Times described Beeple’s style as ‘colorful, digestible pastiches’. Other criticisms focus on the environmental cost of creating the non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that allow an artist to assign a unique code to a digital artwork so that it can be bought and sold using blockchain technology. The crypto artist Memo Akten has calculated that the carbon footprint for minting a single NFT is around 100 Kg of CO2, equivalent to a 2 hour flight from London to Frankfurt.

Proponents of crypto art claim that it is a democratising force, giving artists and customers the ability to by-pass traditional gatekeepers of the art world. Not only that, but the digital platforms they are traded and displayed on are easier to access than physical galleries, offering an opportunity for innovative cultural institutions to find new ways to share, and benefit from, their collections. The British Museum, for example, has partnered with the French NFT platform LaCollection to explore ways of monetising their digital collections (although there remains a lack of evidence that NFT’s are the answer to this problem).

What is Crypto Art?

Crypto art’s aesthetic roots can be traced back to pop art of the 20th century, particularly in its embrace of consumerism and the replication of content. More recent influences include algorithmic or procedurally generated art, where computer code generates a potentially infinite number of images based on a set of fixed inputs.

The core concept of crypto art is that an artist creates an image, almost always pixel based. The artist then ‘mints’ the image, creating a unique code that is associated with the artwork, and stored on the blockchain. Blockchain technology is theoretically perfectly transparent because everyone with access to the blockchain can view all the other transactions that take place on the system. This means that one person’s claim to ownership of a piece of art, stored as a unique code on the chain, can be verified by all the other users. The ‘original’ image itself, whatever that means in a digital context, is still replicable, and can be copy and pasted and downloaded by whoever can find it on the internet. It is the ownership of the image, rather than the image itself, that is valued, and that is the thing that is bought and sold.

What is the value of (crypto) art?

The discourse around Beeple’s NFT auction was reminiscent of other debates triggered by controversial conceptual art works, from Marcel Duchamps’ Urinal Fountain to, more recently, Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, an overripe banana taped to the wall with duct tape.

If an NFT is a pointer to a work of art, not the work of art itself, the same can be said about some conceptual art. It is the idea that is being traded, rather than any material object. By purchasing one of the several copies of Comedian, for example, collectors bought the concept of the piece. This included a certificate of authenticity and instructions on how to install and preserve the artwork, including replacing the banana whenever necessary.

In the case of crypto art, the artist gives their digital artwork value by endowing it with a unique attribute. This is similar to how an author can increase the value of a book just by signing it, or a collectable baseball card gains value because of some rare fault in manufacture. The NFT, by providing a uniquely verifiable digital ‘signature’, gives value to a piece of crypto art.

Thus, compared to other art forms, the value of a piece of crypto art is, in the first instance at least, more explicitly related to ownership, and not just to aesthetic value or historical importance. Of course, any piece of art, however ancient or famous, can be given a price tag. Auctioneers, art dealers, galleries and museums have been assessing the financial value of, and trading, art for centuries. But when these commercial interactions take place, the actors involved still claim that aesthetic assessments are being made as well. Bad art, they might claim, would be worth less money than good art.

Crypto art, by tying its financial value so closely to ownership of an artwork, shines a spotlight on the relationship between art, finance and aesthetics. Indeed, the implication of NFTs is that in purchasing a digital certificate of ownership and authenticity, in the words of Simon Mackenze and Diāna Bērziņa, ‘that might be all you are getting’. It is the claim of ownership of a piece of art, not the artwork itself, that is being bought.

Crucially, Crypto Art, by creating art with a collection of pixels, identified by a unique code on a blockchain, challenges us to think more critically about the meaning and value of owning intangible digital objects. And while the NFT craze might pass, blockchain technology has the potential to allow us to reflect on the regulatory and economic foundations of the art market and the creative industries.

_________________________________________________

Thumbnail image by SIMON LEE on Unsplash

Hero image by Arthur Mazi on Unsplash

Related Blogs

Taking stock of the Creative Industries Sector Plan

We summarise some of the key sector-wide announcements from the Creative Industries Sector Plan.

Why higher education matters to the arts, culture and heritage sectors

Professor Dave O’Brien, Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries at University of Manches…

What does the 2025 Spending Review mean for the creative industries?

A read out from Creative PEC Bernard Hay and Emily Hopkins On Wednesday 11th June the UK Government …

Bridging the Imagination Deficit

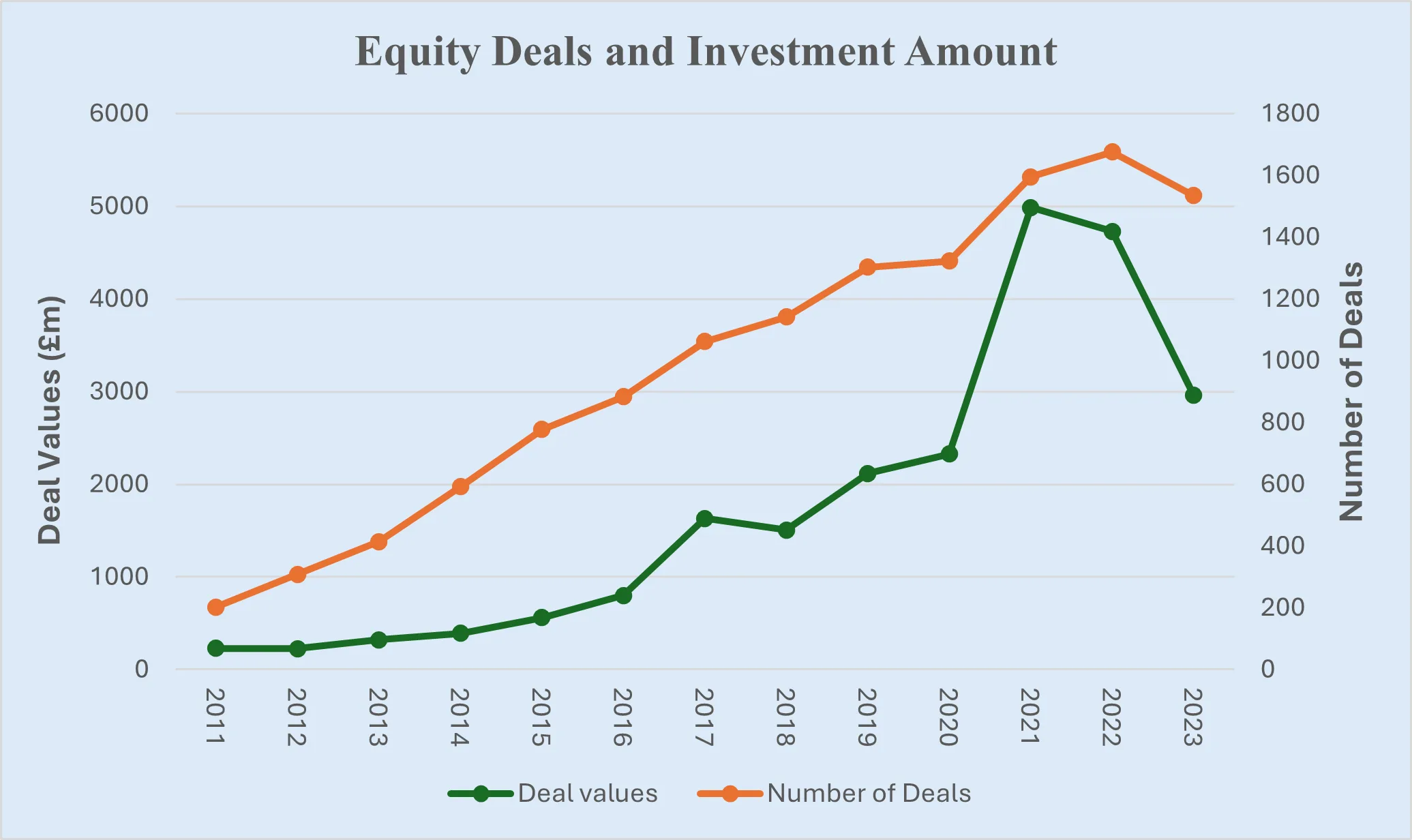

The Equity Gap in Britain’s Creative Industries[1]. by Professor Nick Wilson The creative industries…

Why accredited qualifications matter in journalism

Journalism occupations are included on the DCMS’s list of Creative Occupations and, numbering around…

All Together Now?

Co-location of the Creative Industries with Other Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Dr Josh Siepe…

The Mahakumbh Mela, India, 2025

The festival economy: A Priceless Moment in Time Worth GBP 280 Billion in Trade Jairaj Mashru looks …

Class inequalities in film funding

Professor Dave O’Brien, University of Manchester, Dr Peter Campbell, University of Liverpool and Dr …

Creative self-employed workforce in England and Wales

Dr Ruoxi Wang, University of Sheffield and Bernard Hay, Head of Policy at Creative PEC Self-employed…

What just happened to funding for culture in Scotland?

First the facts: Creative Scotland announced the outcome of its new Multi-Year Funding Programme on …

Copyright and AI – a new AI Intellectual Property Right for composers, authors and artists

Background The new technology landscape emerging from the super rapid progress in developing AI, Gen…