Timely exploration of copyright law and AI generated creative content

The use of technology to create art is centuries old. This has generated legal and cultural debates in the past for example with the invention of photography and later when interactive computer games were introduced. Over time, copyright law has adapted to recognise human “authorship” in the use of these tools. Identifying where the creativity happens in the process of AI-assisted creation is an urgent question. In this blog I compare the legal situation in the USA and the UK, where differing approaches have implications for technology and creative industries policy, including liability of content platforms.

At the core of the debate is the question of whether artistic content which has been produced with AI input should be protected by copyright law. The artistic content produced by AI systems – such as Midjourney, ChatGPT and Dall-E – have been described as both mechanical and creative, depending on one’s view on the technology and the defining qualities of human artistry.

Applying objective criteria such as ‘novelty’ or ‘degree of transformation’ could support the inclusion of AI-assisted content within a pragmatic definition of creativity. On the other hand, copyright law is “anthropocentric”, with regulation often implying or asserting that copyright protection can only lie with a human author.

The U.S. Copyright Office (USCO) stance

In a series of decisions and guidance issued in 2023, the USCO has clarified that works created with substantial AI input are not eligible for copyright protection in the United States. Since 1973, it has been the official position off the USCO that in order to benefit from copyright protection, works must be attributable to a “human agent”. Under the new guidance, “AI-generated content that is more than de minimis” should be explicitly identified and excluded from registration. In other words, the human-made aspects of AI-generated works, such as “prompt instructions”’, are eligible for copyright protection, while any output from, such as images in a text-to-image model like Midjourney, are not.

The artists of two works that were denied copyright registration, a graphic comic titled Zaraya of the Dawn, and a painting titled Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, each individually appealed the USCO decisions. In both cases, the artists referred to the quantity and specificity of prompts used to instruct Midjourney to generate seed images that were used in the final artworks. For example, the registrant of Théâtre D’opéra Spatial argued that his use of Midjourney was akin to use of any other artistic tool. He had directed the creation of the image by “enter[ing] a series of prompts, adjust[ing] the scene, select[ing] portions to focus on, and dictat[ing] the tone of the image.” The USCO recognised prompts as a literary work of human authorship, but not the resultant image.

In the Zaraya registration case, the USCO argued that “the process is not controlled by the user because it is not possible to predict what Midjourney will create ahead of time.” The artist, Kashtanova objected that she has played an active role in guiding the creation of the images through “hundreds of thousands of prompts” and through making corrections to some of the outputs using image-editing software. The USCO was unconvinced, asserting that “the process described … makes clear that it was Midjourney – and not Kashtanova – that originated the ‘traditional elements of authorship’ in the images”. The USCO Review Board noted that it was possible for copyright to subsist in a work where a computer was used as an “assistive instrument”, but the line demarcating human-directed authorship with mere assistance from AI is unclear.

The situation in the UK

Section 178 of the UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act (CDPA 1988) enables copyright protection in works generated by a computer in circumstances when there is no human author of the work. However, since copyright cannot vest in machines or non-human actors, the resulting author of a computer-generated work is the person “by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken.” In this case, copyright term is reduced to 50 years, and no moral rights apply to the work. The language of the CDPA is not clear whether in making the arrangements, the ‘human stand-in author’ must exhibit the same skill labour and judgment required to meet the threshold of originality required for copyright to apply in traditional works. It is therefore uncertain whether arrangements such as prompts need to be sufficiently original, exhibiting enough “free and creative choices” for a human to meet the originality requirement for copyright, or whether this is overridden by a lower standard of originality for “computer generated work”.

The law is also unclear on the line drawn between computer-generated and computer-assisted work. In other words, to what extent must the computer act alone, without input from a human in order for a work to be considered computer-generated, rather than a work of traditional human authorship? Different interpretations of “arrangements necessary for creation” mean authorship could conceivably rest with the company or programmers who designed the AI system. Assigning authorship has implications for liability: some platforms are eager for users to bear liability for any infringing outputs they create, while companies like Adobe have made assurances that users will not be liable for copyright infringements arising from the use of their AI tools.

Implications for creative industries policy

There are potential policy harms and benefits to acknowledge in each approach. As I have argued elsewhere, the output of generative AI is qualitatively and quantitatively different even from disruptive capabilities of digital tools we are already familiar with. The ease and speed with which AI-generated works can be created means that there may soon be more copyright-protected creations in circulation than ever in human history. As Vicki Strachan argues, gaining copyright in an AI-produced image may not have many practical benefits for creators or firms. That is because others can quickly generate their own similar content with the same low effort.

This has led some legal theorists to advocate for placing AI-generated outputs in the public domain, arguing that the proliferation of private rights in such voluminous output may stifle innovation because new creators will fear encroaching on someone else’s copyright. On the other hand, artists who are passionate about the potential of AI technology have argued that the directive and curatorial instructions they use to guide AI tools requires skilled labour and judgment that is worthy of recognition and protection.

Innovation-focused policy makers may view the ability to own and license AI-assisted creations as favourable to economic growth. What is urgently needed is evidence on the likely impacts of AI generated work – whether copyright protected or not – on the lives and livelihoods of creators.

Image by Shahadat Rahman via Unsplash.

Related Blogs

Taking stock of the Creative Industries Sector Plan

We summarise some of the key sector-wide announcements from the Creative Industries Sector Plan.

Why higher education matters to the arts, culture and heritage sectors

Professor Dave O’Brien, Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries at University of Manches…

What does the 2025 Spending Review mean for the creative industries?

A read out from Creative PEC Bernard Hay and Emily Hopkins On Wednesday 11th June the UK Government …

Bridging the Imagination Deficit

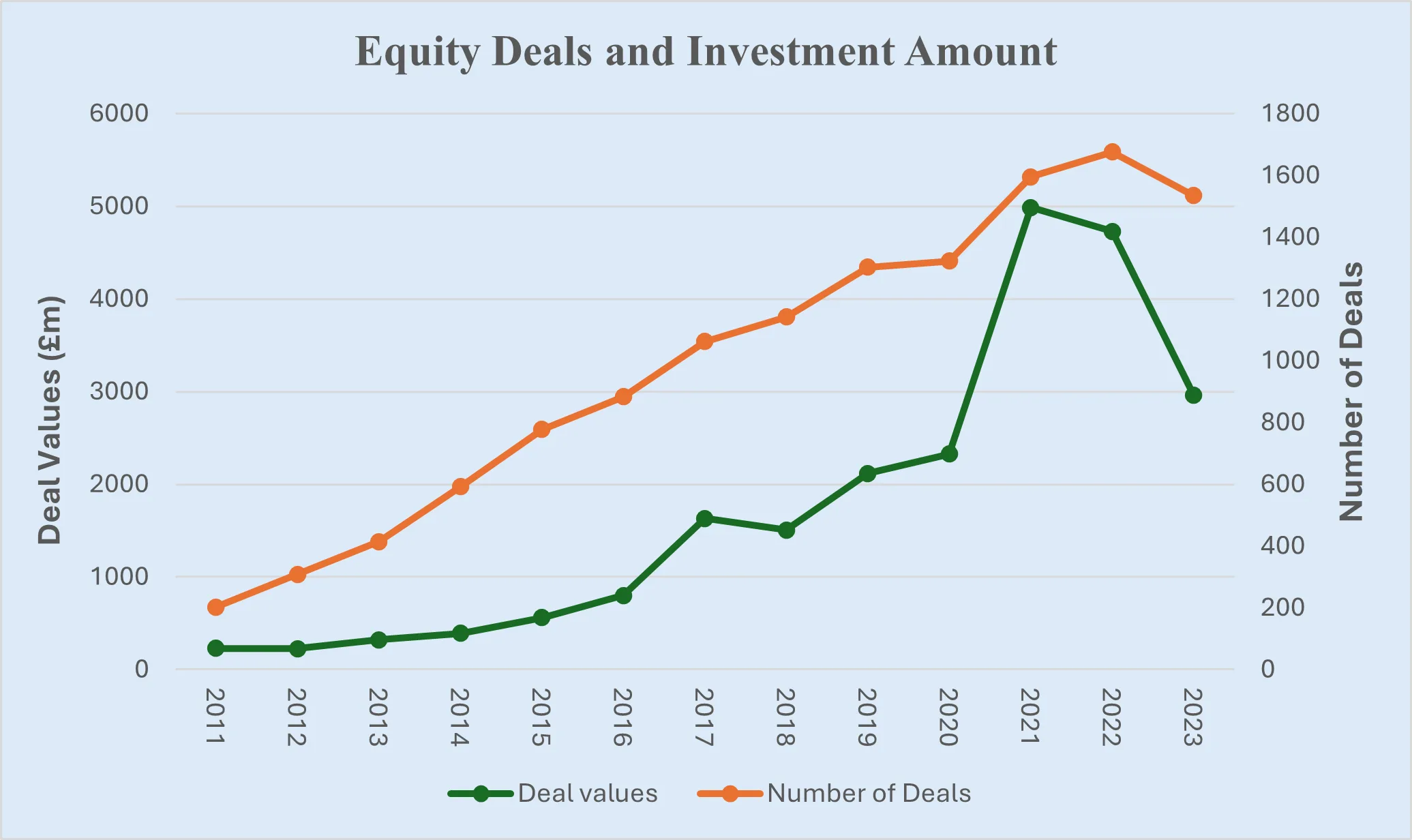

The Equity Gap in Britain’s Creative Industries[1]. by Professor Nick Wilson The creative industries…

Why accredited qualifications matter in journalism

Journalism occupations are included on the DCMS’s list of Creative Occupations and, numbering around…

All Together Now?

Co-location of the Creative Industries with Other Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Dr Josh Siepe…

The Mahakumbh Mela, India, 2025

The festival economy: A Priceless Moment in Time Worth GBP 280 Billion in Trade Jairaj Mashru looks …

Class inequalities in film funding

Professor Dave O’Brien, University of Manchester, Dr Peter Campbell, University of Liverpool and Dr …

Creative self-employed workforce in England and Wales

Dr Ruoxi Wang, University of Sheffield and Bernard Hay, Head of Policy at Creative PEC Self-employed…

What just happened to funding for culture in Scotland?

First the facts: Creative Scotland announced the outcome of its new Multi-Year Funding Programme on …

Copyright and AI – a new AI Intellectual Property Right for composers, authors and artists

Background The new technology landscape emerging from the super rapid progress in developing AI, Gen…