Industry Champion Ve Dewey writes on the importance of responsible AI in the creative industries. The contents of this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Creative PEC.

Alarms are sounding across every sector at the exponential growth of AI, but nowhere is the urgency more profound than in the UK’s creative industries. A key growth sector in the Government’s Industrial Strategy, employing 2.4 million people and contributing £124 billion to the UK economy in 2023, it remains a cultural cornerstone of democratic life.

Nearly two decades ago, UNESCO’s 2005 Convention affirmed cultural diversity as a “defining characteristic of humanity” and essential to pluralistic societies. It recognised cultural expression as rooted in creativity and sustained by free expression, imagination, and dialogue. That framing feels even more urgent today. As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, we must ask: Who gets to create? Whose voices are erased? And what systems shape the future of expression?

With my interdisciplinary design background, I see AI not as technological disruption, but as a systemic design challenge. We are not just building tools, we are designing interconnected infrastructures that shape how people live. The stakes are generational.

Informed by sociologist Helga Nowotny’s idea of “civilisation as geometry”, that the design of systems organises our coexistence, AI becomes a force to reshape meaning. Yet despite efforts, like DeepMind’s inclusion of ethicists, we still lack structural governance to protect imagination, creative agency, and originality. As Professor Yoshua Bengio writes, avoiding the centralisation of AI power requires fundamentally rethinking how these systems are built, shared, and governed.

Beyond Tools: Responsibly Designing AI Systems

If AI is a systems problem, then policy and public discourse are part of it. Encouragingly, “responsibility” is gaining ground. At London Tech Week 2025, Keir Starmer said AI should “make us more human.” Professor Neil Lawrence, DeepMind Chair of Machine Learning University of Cambridge, has noted we need to be “experts in humans, not in AI.” But traction is not transformation.

Responsibility is still too often treated as cosmetic. At a recent All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on the Future of Work meeting at the House of Lords on the Creative Industries and AI, artists described how their voices were cloned, music sampled, and livelihoods reshaped, without consultation or consent.

Meanwhile, AI companies like Anthropic claim to make tools “with human benefit at their foundation,” and OpenAI promises AI that “benefits all of humanity.” Yet these ideals often clash with lived experience. On 17th July 2025, Emily Ash Powell, former Head of Copy at Bumble, posted that all copy, design, video teams were cut due to AI. “You won,” she wrote. “I hope they make you happy.” Responsible AI must reconcile these contradictions, not with promises, but with design.

Principles for “Good AI” in the Creative Industries

For me, Responsible AI means designing systems that are inclusive, transparent, and accountable; supporting, not eroding, authorship, cultural diversity, and democratic participation in the creative sector – or else we risk undermining the very foundations it claims to protect.

Drawing on my research, lived experience, and sector observation, I propose four core pillars to guide what Responsible AI looks like for the creative sector.

1. Inclusive by Design

Diverse stakeholders must be involved from design to deployment, especially those most impacted. In the creative industries, this means centring creative workers and underrepresented voices within both design processes and governance structures.

A leading example is the Inclusive AI Lab, co-founded by Laura Herman and Professor Payal Arora. Rooted in feminist and cross-cultural design, the Lab embeds inclusion through participatory governance and community-led research. In Decolonizing Creativity in the Digital Era, they show how dominant AI systems flatten cultural nuance, forcing non-Western creatives to “hack” the system.

The international context adds urgency. In July 2025, the U.S. signed an Executive Order targeting so-called “woke AI”, effectively removing equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) from federally supported AI development. With most foundational models built by U.S. Big Tech, the implications for AI use in the UK and Europe could be profound. This underscores the need for agile governance frameworks that evolve with shifting political, cultural, and technical conditions, embedding pluralism, specificity, and rights-based inclusion from the outset, not as a reactive fix.

2. Human-centred Use

Authorship must remain central. Take Springboards, a Queensland-based startup founded by “creatives who learned to code.” Its platform amplifies ideation without automating creativity. As the founders put it: “We built Springboard to help creatives think big, explore boldly, and stay original.” Similarly, &Walsh’s branding for Isodope used DALL·E, but under clear human-led direction.

This ethos runs counter to much of Big Tech’s rhetoric. Whilst companies tout “amplifying potential,” creatives continue to see their roles diminished. Human-centric AI must go beyond interfaces, it must protect authorship, labour, and agency.

3. Transparent and Accountable

Transparency means more than publishing a charter. Creatives must know how their work is used, and be able to challenge misuse. In summer 2025, WeTransfer, the file-sharing platform long associated with championing the creative industries, quietly updated its terms of service to permit user content to be used for AI training. The backlash was swift. Although the company reversed course within days, the incident exposed how easily creative trust can be eroded when transparency is vague or retroactive. Some firms, like Adobe, are starting to link governance to creative risk. But these remain the exception. As Madhumita Murgia has explored (2024), opacity in AI systems isn’t just a technical issue, it is a form of power that can obscure accountability and concentrate control.

4. Sustainable by Design

Following Nowotny’s thinking, AI is now part of our civic infrastructure, and its architecture must sustain, not erode, our cultural and ecological ecosystems. Responsible AI must be governed, not just optimised, and designed for long-term interdependence over short-term scale or optimisation.

AHRC’s BRAID programme offers a model of sustainability-led policy. Bath Spa University’s BRAID demonstrator project, “Exploring sustainability and environmental resilience”, addresses AI’s environmental impact through governance tools, not just technical fixes. Meanwhile, EPFL, ETH Zürich, and the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre are building a sovereign open-source multilingual model on public infrastructure. It exemplifies AI designed for trust and regeneration, not extraction.

The real question is not whether we “win”, but what are we willing to sacrifice. When creative industries and societal thresholds are sidelined for speed and supremacy, it is not just technical systems at risk, but the cultural and ecological futures they were meant to serve.

Designing Governance, Not Just Guidelines

Creativity is not a product, it is a process: iterative, relational, and deeply personal. Responsible AI must safeguard the conditions that enable cultural expression. As Karen Hao has written, today’s AI empires rely not on force, but on opacity and automation without consent. Without new governance models, we risk reproducing extractive colonial logics in our cultural systems.

At the APPG session, one speaker cited Singapore’s anticipatory workforce policies, a model of cross-sector, design-led governance. The UK has a choice. We need similarly generative, sector-informed processes for the UK’s creative industries. Yet few organisations invest in the infrastructure to make “Responsible AI” real. As ethicist Alice Thwaite put it, responsibility is “out the window”, spoken of, but disappearing in practice.

As John Dewey argued, from Democracy and Education to Art as Experience, creativity is not an ornament of public life, but one of its foundations. Through imagination, experimentation, and expression, people learn to participate in, shape, and co-create democratic life. When AI systems automate authorship or displace creative agency without consent, they do not just threaten livelihoods; they undermine the very capacities upon which democracy depends.

And as Albert Einstein warned:

“The benefits that the inventive genius of man has conferred upon us in the last hundred years could make life happy and care-free, if organisation had been able to keep pace with technical progress.”

For the creative industries, the stakes are especially high. Without inclusive, participatory, and creatively grounded governance, we risk a future where imagination is sidelined and originality flattened by optimisation. The UK’s creative sector must not be an afterthought. It should be designed as a cornerstone.

Ve Dewey is a globally networked design leader whose career has been at the intersection of technology, design, and innovation. She has succeeded across industry, the third sector, and academia for globally iconic creative brands and organisations, such as Mattel Inc. and Adobe. Over a 15+ year career, Ve has championed inclusive approaches to design leadership, organisational change, and AI. Find out more.

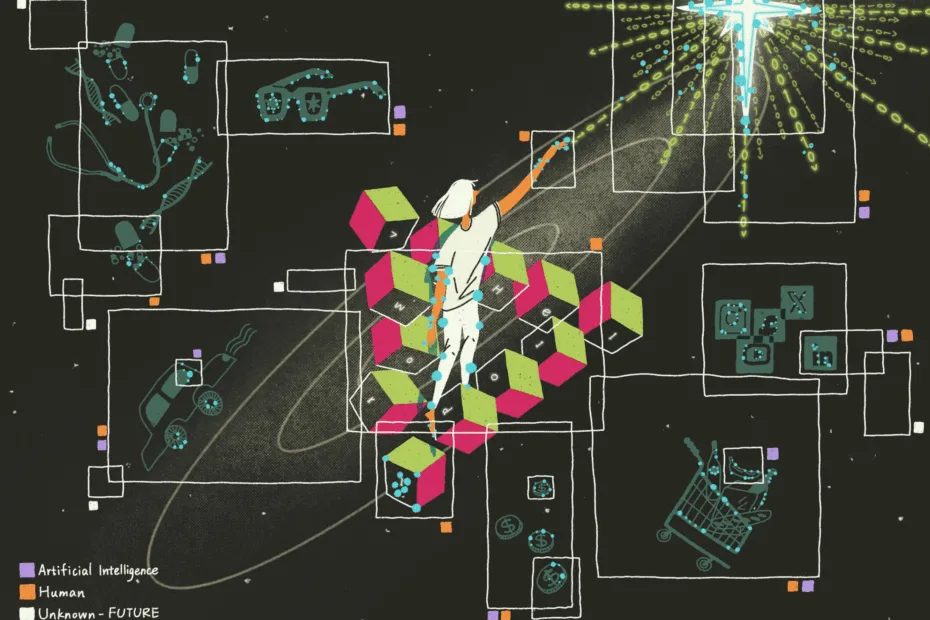

Main Image: Yutong Liu & The Bigger Picture / AI is Everywhere / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0