One bright spot in an otherwise uncertain year for immigration policy, was the expansion in October 2019 of the UK’s Shortage Occupation List (SOL) to include many more creative industry roles. Prior to this, the list contained only selected occupations like animators, compositing artists and production managers, now all occupations within several Standard Occupational Classifications (SOC) codes such as for Artists (3411), Graphic Designers (3421) Arts Officers, Producer and Directors (3416) have been added to the list. With these and other revisions, it’s thought that 9% of all potential jobs are on the expanded SOL; up from around 1%. Recruitment of non-EEA citizens to these SOL roles currently receives priority in the visa system and avoids the need to conduct a time-consuming and often pointless Resident Labour Market Test (RLMT), to prove that no suitable UK workers exist.

It is ironically coincidental that these SOL roles are the same creative occupations identified by the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC) as being very likely to grow as a share of the workforce by 2030, by virtue of being resistant to the march of automation. In fact, the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) has already declared them as being in national shortage, and that’s even before the major tightening of immigration policy expected when free movement ends following Brexit. This should be sounding a red alert for immigration policy but also raising concerns over the low priority given to creative subjects in the education curriculum, which is restricting the supply of suitable home-grown talent.

The existence of the SOL is not assured beyond 2020, however. The proposals in the 2018 Immigration White Paper (IWP) seemed to render it almost irrelevant by abolishing quotas and the RLMT. Whilst these moves were welcomed, the IWP also threatened to impose a £30k minimum salary threshold for both EEA and non-EEA skilled migrants. Rather than creating a skills-based system, the IWP proposals would have produced an expensive regime where the lever of control over skilled immigration would be an employer’s ability to afford the visas for the international talent vital to their success.

Salary is a very poor measure of skill level. A single minimum visa salary threshold for all industries does not consider structural differences in remuneration across sectors and disenfranchises areas such as hospitality, construction, health and social care, as well as the creative industries. However, there has been a change of plan and the IWP may be already be in the shredder. The Johnson government’s announcement to implement a Points-Based visa system could present the opportunity to reframe the debate about skilled migration to criteria other than salary, as more appropriate measures of the visa applicant’s ability and worth to the UK economy.

An appropriately structured system should provide a multiplicity of ways to receive qualifying points for a visa, such as a combination of a confirmed job offer, educational qualifications or previous experience, rather than just using salary alone. Creative sector employers are hoping that EEA and non-EEA migrants to the UK who are coming to take up SOL roles will score highly in the points system, but as yet there are no detailed proposals, nor is there any indication whether high minimum salary thresholds will also play a part, or not.

An unsympathetic combination of salary thresholds and points-based criteria could be highly damaging for businesses seeking to attract the world’s best talent to the UK. It seems that we won’t know the government’s full intentions until the MAC reports their findings in January 2020 following their recent consultation. We can only hope that its recognition that key creative roles are in national shortage is reflected in the new system too. It’s going to be an anxious wait.

The PEC’s blog provides a platform for independent, evidence-based views. All blogs are published to further debate, and may be polemical. The views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent views of the PEC or its partner organisations.

Related Blogs

Taking stock of the Creative Industries Sector Plan

We summarise some of the key sector-wide announcements from the Creative Industries Sector Plan.

Why higher education matters to the arts, culture and heritage sectors

Professor Dave O’Brien, Professor of Cultural and Creative Industries at University of Manches…

What does the 2025 Spending Review mean for the creative industries?

A read out from Creative PEC Bernard Hay and Emily Hopkins On Wednesday 11th June the UK Government …

Bridging the Imagination Deficit

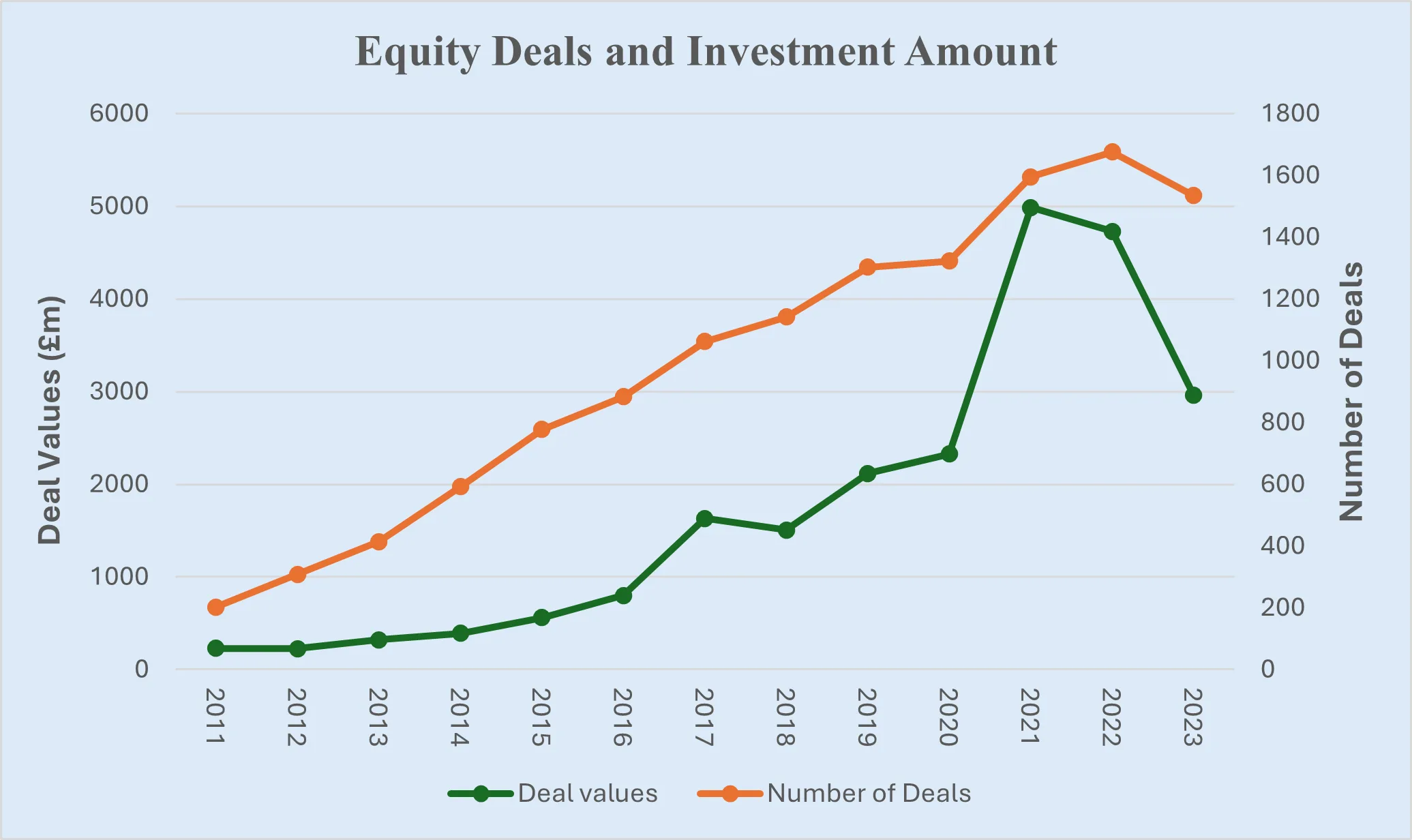

The Equity Gap in Britain’s Creative Industries[1]. by Professor Nick Wilson The creative industries…

Why accredited qualifications matter in journalism

Journalism occupations are included on the DCMS’s list of Creative Occupations and, numbering around…

All Together Now?

Co-location of the Creative Industries with Other Industrial Strategy Priority Sectors Dr Josh Siepe…

The Mahakumbh Mela, India, 2025

The festival economy: A Priceless Moment in Time Worth GBP 280 Billion in Trade Jairaj Mashru looks …

Class inequalities in film funding

Professor Dave O’Brien, University of Manchester, Dr Peter Campbell, University of Liverpool and Dr …

Creative self-employed workforce in England and Wales

Dr Ruoxi Wang, University of Sheffield and Bernard Hay, Head of Policy at Creative PEC Self-employed…

What just happened to funding for culture in Scotland?

First the facts: Creative Scotland announced the outcome of its new Multi-Year Funding Programme on …

Copyright and AI – a new AI Intellectual Property Right for composers, authors and artists

Background The new technology landscape emerging from the super rapid progress in developing AI, Gen…