Can art play a role in the intersection of climate science and policy? I have been researching this question over the years, drawing on my experience in policymaking, my visual arts practice, and my role as co-Head of the UK’s Policy Lab. There are theoretical reasons why art may inform policy, for example drawing on Cairney and Kwiatkowski’s argument that ‘rational’ information inevitably intermingles with emotions, feelings, values and beliefs in guiding people’s decisions; and, arguably, practical examples of it, from Blue Planet II to the photography of Lewis Hine. The Arts and Humanities Research Council and Clore Leadership sponsored me to explore this further, drawing in particular on the expertise of the Social Design Institute at the University of the Arts London.

This Autumn, I ran an event/experience which presented a physical manifestation of the research. Glass House explored climate science through an arts and design lens, then brought together small groups of people to ask: what policy do we need to do as a result?

Layers of Bangladesh for example presented five glass slides showing different types of information relating to the impacts of climate change. Sea level data and rainfall is overlaid with economic and population data. The work takes as a reference point interactive data visualisations, where data overlays can be toggled on or off. It aims to playfully subvert this digital tool by rendering Bangladeshi data on recycled greenhouse panes donated to the artist by a Walthamstow allotment holder.

The artwork intends to gently prompt the viewer to consider the relationship between climate factors and more socio-economic drivers of climate vulnerability. In doing so it explored one of the effects of art I identified in my research that was relevant for policy: the cognitive impact of art, its ability to raise awareness of issues and provide information which people otherwise may not have found or be aware of. Layers of South East Asia represented a human-sized counterpoint to this, and aimed to examine another effect of art: the multisensory – visual, physical, kinaesthetic, aural, haptic and so on – interpretation of a policy idea or issue. The three panels showed changes in rainfall, flooding and population in the region. Attendees noted how their own height, their physicality and how they moved in relation to the three panels changed their understanding of how the evidence relating to climate change mapped onto parts of South East Asia.

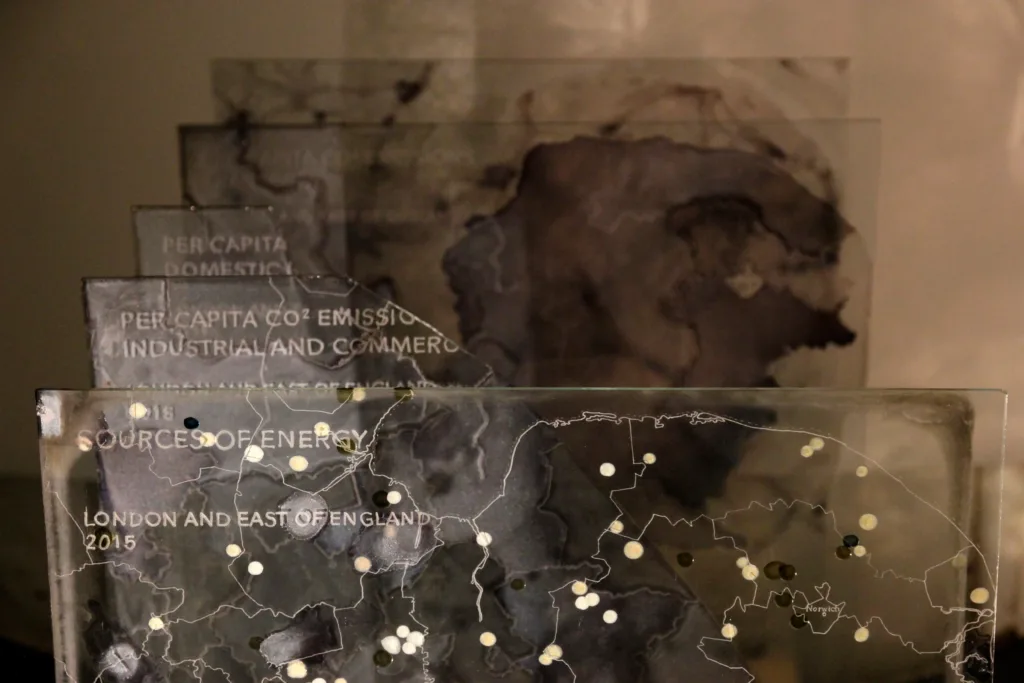

Whilst the previous two layered pieces inquired into the consequences of climate change, the third looked at the energy systems which are intrinsically linked with the environment. Layers of East of England includes data relating to sources of energy in the region, and the carbon emissions associated with transportation, domestic and commercial energy use. As with Layers of Bangladesh, and indeed all of the artworks, the data is depicted on recycled greenhouse glass. Whereas previously I worked hard to polish and grind the panes back into a pristine state, for this artwork the glass is as originally found, including a patina of grime and broken edges. Here the materiality of the piece speaks to another effect of art that is relevant for policymaking: its emotional impact.

Leurs and Kroodsma note that the biggest challenge of the digital age for communicating science is the need to move from a ‘broadcast’ model to a ‘conversation’ model. Many artworks provide a framing for dialogue and discussion, but it is particularly integral to some traditions – for example the”relational aesthetics” movement described by Nicolas Bourriaud. The final piece in the show brought together these threads, and explored whether art can play a role in the relationship between science and policy via the creation of dialogical space. Climate Data Discovery deploys a method which I have used many times in Policy Lab. Rather than expecting individuals to read lengthy reports or sit through long presentations of evidence, the installation instead arranged 40 pieces of climate evidence around a space. Participants looked at the information in their own time, focusing on what they found interesting. They were asked to answer on a card “What policy needs to happen, and why?” – but only after sitting and talking about the issues in a group with random strangers. The fact that the group engaged with the same collection of artefacts provided a common starting point for their discussion. The fact that they all brought their own perspectives, values and biases made it richer. The participants, talking, was the ultimate work of art in this show.

Chairs possess a strange power in art exhibitions. Often absent, when present they usually back against each other, facing the artwork. Turning those chairs inwards is a technique that I borrowed from Alistair Hudson’s Arte Útil informed exhibitions at the Manchester Art Gallery. Rather than demanding the viewer’s hushed reverence to the artwork, the chairs suggest that the artworks are a starting point for a discussion. Here we see the application of Arte Útil in the context of climate policy. The term translates roughly as ‘art as a tool’, and in this case art can be a tool for developing creative, emotionally attuned and participatory policy on climate change.

As a final twist, the cards were collected at the end and engraved on shards of broken glass before being displayed in a growing, iterative, participatory artwork at the end of the space. My next step is to analyse the ideas suggested on these shards. If this blog has sparked your imagination, here are some possible next steps for you:

- If you are interested in supporting an innovative project exploring the deployment of new techniques in policymaking please get in touch with Policy Lab.

- If you are specifically interested in displaying or incorporating Glass House please contact me.

- You can read more about the underlying research on the role of art and policy here.

- You can see Layers, Bangladesh at the Terre Verte gallery in North Cornwall until December 4th 2021.

This climate change initative is still at an early stage – if you would like to stay up to date with our plans and latest research, sign up to our newsletter.

Hero image credit

Thumbnail image credit

Related Blogs

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

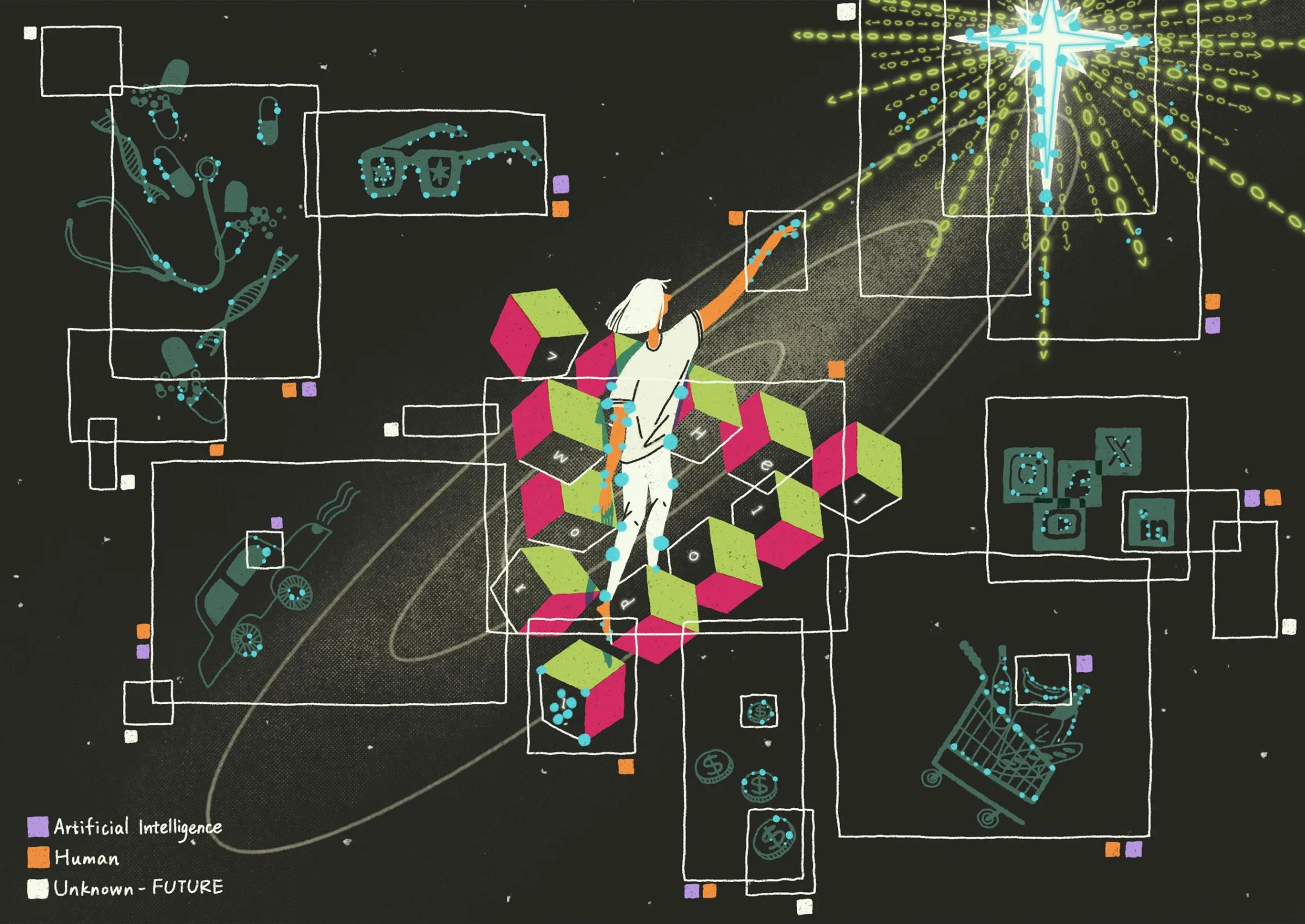

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…