This week we published some of the insights on cultural consumption during the UK’s COVID-19 lockdown from our Consumer Tracking Study, a collaboration with the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) and the research agency, AudienceNet. The report draws on data collected over the period from 9th April to 24th May 2020, asking a panel of consumers aged 16+ detailed questions about their online cultural experiences in the preceding week. This means that the week 1 survey responses relate to the week beginning 2nd April. So one of the study’s strengths is in providing rich insights about the public’s experience from fairly early in lockdown (which the UK commenced on 23rd March). Another strength – possibly making it unique – is that we followed the same cohort of individuals, though survey attrition meant that the sample declined from 3,863 in week 1 to 1,076 in week six. Each week we applied weights to produce nationally representative estimates in our published tracker reports.

So what did we learn?

- Digital culture has mattered to people in lockdown

Between one third (in the case of video games) and two thirds (in the case of film) were engaging digitally when we began fieldwork. And these shares were generally higher than was the case in May 2019, according to the IPO’s OCI Annual Tracker, using identical questions though with a different sample. While we cannot say for sure if consumption had grown early in lockdown these comparisons are suggestive that it may have done. Certainly we found that the vast majority of the public – 90 per cent in the case of music – agreed that culture helped them deal with challenging life circumstances such as those that had arisen with COVID-19. These consumers reported to having spent very significant amounts of time consuming cultural content each day: over the study period, reading books on average for two hours; listening to music between two and a half to three hours; watching film for two and a half to three hours; playing video games for three hours, and watching TV for three to four hours.

2. The digital culture class divide that existed before lockdown may have widened further

The share of the public consuming digital culture generally increased for all socio-economic groups, but more slowly for the ‘working class’ (C2DE) than the ‘middle class’ (ABC1) in areas like TV and music streaming. The sample already by definition excluded those without access to the internet so this added dimension of digital class division in culture is concerning.

3. Those working from home were more likely to consume content than those who had stopped working

Despite having more time in principle, economic factors such as lower income and greater financial uncertainty are likely to have been important. Socio-demographic differences are also part of the explanation. For example, it turns out that self-isolating consumers were generally the least likely to engage with digital content (with the exception of e-books) and older people were disproportionately self-isolating – an age group that is disproportionately less consuming of digital culture (again with the exception of e-books). Self-isolators may also of course have been too ill to engage! Keren Nicol, a furloughed Marketing and Communications Manager at Citizens Theatre, offers an intriguing interpretation on Twitter:

“It takes confidence and security in our own world to enter in to imagined others’ through literature, drama or film. All things that are lacking in redundancy/furlough”.

4. The pandemic has boosted everyday content creation

Roughly one quarter of the public were creating or posting online content each week and six per cent reported having done so for the first time in the six-week period, taking the overall share of those who had ever done so from 50 per cent to 56 per cent: the majority of the UK public are now digital content creators.

5. Lockdown appears to have boosted the long-run trend for streaming to outgrow downloading

In the case of film, 46 per cent of respondents reported in the first week of the survey to have streamed in the past week, much larger than the 34 per cent who had reported having streamed in the previous three months in May 2019. In the case of music, the equivalent numbers were 43 per cent and 40 per cent respectively. An earlier PEC research report studying longer term trends using the IPO’s OCI Tracker showed that from 2013 to 2018 streaming eclipsed that of downloading for film, TV and music and that the gap edged forward year by year.

6. The picture on illegal vs legal access to content is messy

Comparing the percentage of respondents who had used at least one illegal source to access content in the previous three months in the first week of the survey with the equivalent question in May 2019 may indicate what has happened in lockdown. The picture is mixed: some categories saw little change (streaming music and downloading TV); some saw a decrease (streaming and downloading films and streaming TV), and some saw an increase (video games and downloading music).

Over the six weeks, many categories exhibited a similar pattern whereby infringement levels were highest in the first week and then declined, but some (video games and e-publishing) were more variable over time.

The volume of content consumed (for streaming in terms of hours spent and for downloading in terms of individual downloads) generally declined over the six weeks of the study, but this was the case for content from legal as well as illegal sources, making it tricky to assess the extent of cannibalisation of legal sales by illegal activity.

7. The public has embraced non-traditional cultural content

Of all the cultural content types explored, watching filmed performances of theatre, concerts and/or dance shows online saw the biggest percentage share of respondents reporting to either consume this content more frequently or for the first time, followed by looking at art, paintings and photographs online. The proportion overall engaging with this content was sustained but if anything edged down a little over the six weeks.

8. Lockdown has encouraged more people to make physical purchases such as DVDs, console games and books

Interestingly, this pattern appears to have been driven by the younger 16-34 group. The retail sector will obviously be interested to see if it is sustained as lockdown eases, and also whether the ‘forced migration’ we have seen from the high street to online shopping in lockdown reverses.

9. Will these patterns more generally persist?

Thanks to support from the Intellectual Property Office and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), we will learn more from further fieldwork as lockdown eases. We will be reporting shortly on data collected towards the end of last month, and again in August and in September when most children are expected to have returned to schools.

10. Industry needs agile research

Industry needs agile research like this cohort study that can respond to fast changing circumstances. If you’re interested, read more about how we are trying to do that in the PEC.

Photo by JESHOOTS

Related Blogs

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

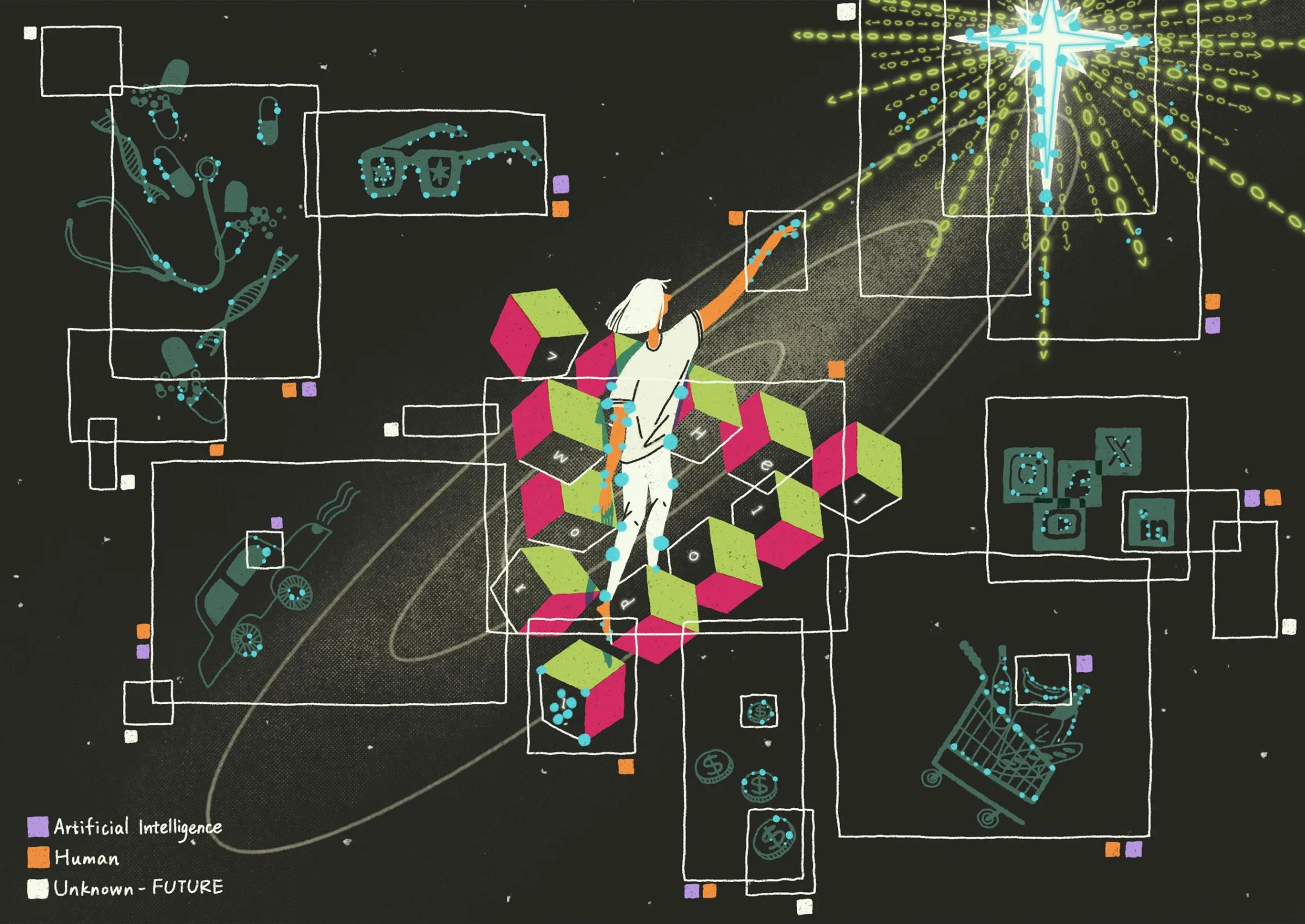

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…

Rewriting the Logic: Designing Responsible AI for the Creative Sector

As AI reshapes how culture is made and shared, Ve Dewey asks: Who gets to create? Whose voices are e…

Reflections from Creative Industries 2025: The Road to Sustainability

How can the creative industries drive meaningful environmental sustainability?