Recent research from UK Music has highlighted the economic contribution that music tourism has made to the UK economy, with the headline figures showing that 29.8 million people attended live music events – with 11.2 million of them classed as music tourists – generating £4.5 billion in direct and indirect spend and sustaining 45,530 full time jobs. Out of that, £211 million remains in the West Midlands. Due to Brexit and COVID-19, the figures post 2020 will undoubtedly be affected, which will have a knock-on effect for Birmingham’s live music sector in particular and the city’s music industry more generally.

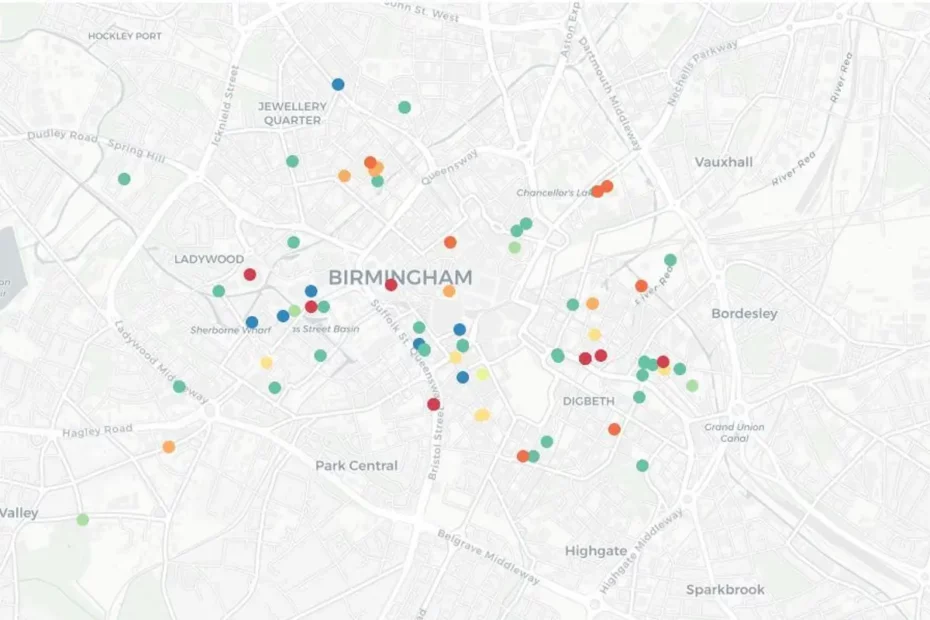

The Birmingham Live Music Project (BLMP) interactive map and database of live music venues in Birmingham launched on 1st June. The map was developed in collaboration between Aston University (Patrycja Rozbicka), Birmingham City University (Craig Hamilton) and Newcastle University (Adam Behr) as part of research that aims to produce the first ever comprehensive map of Birmingham’s music venues. The project aims also to map ‘live music ecology’ and illuminate the interdependencies across different local, national and global actors. The BLMP is part of the ‘UK Live Music Industry in a post-2019 era: A Globalised local perspective’, which is one of the PEC’s first commissioned research projects.

During the preparation of the map, the BLMP team exposed a very mixed picture with regard to what venues are doing and what options are available to them due to the current situation. While some smaller venues, like The Horseshoe Inn (B14 5EL), closed their premises, others (see below) have moved to live music streaming and new forms of individual engagement with their customers, including crowdsourcing.

All live performances across Birmingham are now cancelled. The expectation is that some will make a comeback later this year, promising at least to some degree a packed agenda for November and December. During these uncertain times, some of the local venues (of small to medium capacity) are bringing fans and their patrons together via their online platforms: the Sunflower Lounge (B5 4EG) organizes daily live streaming sessions on Instagram; the Night Owl (B9 4AG) is offering livestreams from their DJs sessions; and Pirate Studios (B9 4EG) is giving over its Instagram channel to Producer Nutty P to chat about production, set ups, and ‘how to keep up sane’– offering a unique opportunity for studio patrons to stay in contact with bands and venues.

Some of the venues exclusively update their benefactors through online posts on Facebook and Instagram, including messages on how the staff are doing, encouraging their followers to ‘stay safe’, and ‘be kind’, as well as keeping hopes alive for a re-opening in near future with new, ‘exciting’ line-ups (see for example: the Facebook page of Hare and Hounds, B14 7JZ). Some of the venues also offer offline delivery of various products and merchandise (for example: DigBrew.Co, B5 5SA, or 1000 Traders, B1 3HE). Venues are encouraging engagement through fundraising and the sale of merchandise, but this is not as widespread in Birmingham as in some other cities and towns (for example, a fantastic crowdfunding campaign by the Boileroom in Guildford, which has already collected more than £20.000).

Insights from the BLMP map show that, as scenes and venues vary across the city, much depends on the resources available (for example, where venues and scenes sit within the furlough scheme). While the majority of the smallest venues and social clubs have suspended their activity, the venues of 150-300 capacity that are particularly important sites in their local areas (for example, the Hare and Hounds in Kings Heath) remain active, albeit on social media channels or through online-ordered deliveries. It is important to notice, however, two characteristics that are especially problematic for the situation in Birmingham: Firstly, if a venue is not doing online deliveries, the majority of their online social media activity is conducted on voluntary basis, with neither artists nor venues receiving direct revenue. Relatedly, a lack of revenue and/or crowdsourcing endangers venues’ ability to maintain their existence and to be able to re-open when restrictions are lifted. Secondly, being in problematic financial shape suggests that some smaller venues (which, based on the BLMP map, are numerous in Birmingham and its suburbs) will not be able to afford the implementation of the likely costly health protocols required for reopening, thereby delaying their re-opening even more.

The situation is challenging for everyone, but the goal of the project is to identify where the most acute (and long term) needs arise. The data collected for the map to date can be extrapolated and used to develop complementary coping policies, allowing for the forecasting of market and industry change and therefore the development of reactive strategies. Long term, the outcomes, findings and replicable working methods deriving from the project will ensure that other regions – and particularly urban centres – will benefit, helping raise awareness of the live music sector and the challenges it faces.

The BLMP research findings – and particularly the data and mapping of the health of the sector in Birmingham – will be of interest and use to various stakeholders in the city, and beyond, to help with their policy and strategy work with agencies such as the West Midlands Combined Authority, Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP, and Birmingham City Council. Beyond cultural policies, the data can impact upon city planning and development policies, licensing regimes, and environmental regulation.

Currently, the mapping is limited to the geographic area covered by B-prefix postcodes – excluding the wider West Midlands and greater Birmingham area – to render the scope of the project manageable and achievable. However, there are plans to expand the map in the future.

If you are interested to find out more about the project, please get in touch with the BLMP team at info@livemusicresearch.org, via twitter @livemusicres or Facebook @livemusicresearch.

Related Blogs

10 facts about Creative Industries growth potential

Discover ten key findings from the report 'High-Growth Potential Firms in the UK's Creative Industri…

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.

When Data Hurts: What the Arts Can Learn from the BLS Firing

Douglas Noonan and Joanna Woronkowicz discuss the dangers of dismissing or discarding data that does…