How those bidding for levelling up funds can find out more about their local Creative Industries

Although there are useful national and regional statistics publicly available to those bidding for levelling up funds, including those available here, it is fair to say that the Creative Industries are not always best served by traditional data sets (e.g. collections of information on employment or trade). This is for a number of reasons, including the number of freelancers and small businesses in the creative industries, which tend to be less well represented in surveys, as well as the fact that the Creative sub-sectors and jobs can be at the cutting edge of new technologies and so are not included in older data sets.

That is why the PEC, UKRI, the CIC and others have taken different approaches to understanding the sector, which may be useful to those looking to understand their local creative industries. This page highlights some of the approaches others have taken to understand the sector, as well as providing a long list of resources for those interested in existing research on the Creative Sector.

In addition, we suggest that any local authorities looking to invest in their creative industries contact anchor institutions (e.g. large public art organisations, universities etc.) who may already have links into the sector. A good start would be to ask your national arts council to be put in contact with publicly funded local arts organisations (PEC research has pointed to the links between cultural organisations and the wider creative industries at a local level), or by speaking to the relevant departments in local universities.

If you have a piece of research that you believe might be helpful to those bidding for levelling up funds more information on how to use and share it is below

Ways to Approach Creative Industries Research

Web scraping

There are limitations to the data that the Government is able to publish about creative companies (a summary of key Government data sets is available here). For example, Government data largely reflects where companies are registered rather than where they actually trade, and companies’ Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes (used by the Government to record a business’s industry) do not always capture their activities accurately. In addition, in order to publish some datasets there has to be a large enough number of companies to ensure sensitive information isn’t revealed.

Collectively these issues mean it can be challenging to get very specific information in terms of type of business or exact location. This is despite the fact that many creative companies are happy to put such information out into the world for public use, often through websites which more clearly describe what they do and where they are based. This is why researchers sometimes use data scraped from creative companies’ websites to better understand certain aspects of the creative industries. Although not all creative companies will have a website, researchers in the PEC consortium have frequently found this is a good way to uncover data about smaller clusters of creative businesses.

For example, the PEC has published research about England’s rural creative industries which uses analysis drawn from data scraped from the websites of 184,791 creative industries organisations in England, from which we were able to extract postcode data of the organisations’ locations. Companies were classified into sectors based on activities described on their websites, and then identified as being in the creative industries using the UK DCMS (2014) definition. We could then identify clusters of geographically close rural creative firms.

Job advert data

Creative occupations (like artists, games designers, directors and publishers) are both a defining characteristic of the Creative Industries, and an important asset to companies outside the creative sector. For example, the design sector employs a large number of designers, but companies outside of the Creative Industries (e.g. in the automotive industry) might also employ designers with similar skills. And, of course, designers may move between a design firm in the Creative Industries, and a design role outside.

Both inside and outside the Creative Industries, it can be challenging to get timely and granular data on the skills demands of employers for every occupation. National data sets are not always able to tell us exactly which skills are being demanded and it is not always possible to link this to other information like salary or region. That’s why some researchers look to job adverts as a useful data source to help them to understand more about which skills are needed in the creative industries.

One example of a piece of research which uses job advert data is a paper by the PEC and Nesta about digital creative skills. The researchers used the data from 35 million job adverts collected by an agency called Burning Glass to help them to identify creative digital skills, and to demonstrate their growing importance in the labour market.

Like any data source, job adverts have limitations. One major drawback is that not all roles in the creative sector are recruited via online job adverts. For example, they may be via auditions, tenders or word-of-mouth. This means that you might not want to use traditional job adverts to measure the skill demands in occupations, particularly those that have high levels of self employment, unless you conceived a piece which looked at online marketplaces which are specifically offering opportunities for freelancers.

Qualitative research

All researchers will acknowledge the importance of quantitative data in understanding the Creative Industries. However, few rely wholly on it to understand the situation in a local Creative Sector. In depth interviews can help policy leaders to understand the specific issues faced by groups that might not be picked up in a survey, and would certainly be difficult to identify in national data sets. Qualitative research can provide nuance and meaning to the trends, attitudinal shifts and numerical values captured by questionnaire surveys. Identifying the experiences of those working in the sector provides greater context to the raw data about local capacity and needs.

In the PEC we have identified a large cohort of ‘industry champions’ who we bring together for informed panels to provide evidence of their working experiences across the sector. Bringing together informants through facilitated workshops and focus groups is a requirement for the co-production of qualitative evidence, and can lead to greater buy-in from participants, though this process must be properly funded in order to work. A further approach is to ensure mixed methods are used, as in research conducted by the University of Manchester for a project run by the Centre for Cultural Value in partnership with the PEC. This brought together qualitative interviews with policy and industry leaders from the GM region with analysis of quantitative data sets on workforce and funding.

We have found it particularly challenging to include freelancers in qualitative research, but their inclusion is often essential to produce accurate results, as they make up a third of the workforce of the sector. We recommend that you put some money aside to pay those freelancers who are giving up their working time to help you better understand the sector.

Survey data

Surveys of all kinds have proved an important methodology to help policymakers, academic researchers, businesses and arms-length bodies to better understand the Creative Industries. They are useful because they can help with a wide range of questions, can give results rapidly, and can target drastically different groups.

One method the PEC has used is to ‘piggyback’ on existing surveys used by others. That can mean paying for additional questions to national or regional surveys. In doing so, you access an archive of information (including sometimes historial) which puts your individual survey in context. The PEC and CIC used this approach in a piece of research which ‘piggybacked’ on the national Employers Skills Survey.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic many industry bodies sought to engage in rapid data collection to understand the impact of the pandemic on businesses. It should be noted that as with qualitative research, surveying requires participants to have some capacity to respond. As a result, one effect of the pandemic was increasing survey fatigue, as more organisations than usual were running surveys to measure the impact of the pandemic. This led to lower response rates and sometimes poor quality data.

There are several challenges when trying to do these surveys, and so the PEC put together a list of useful tips about how to approach survey design, based on years of experience of designing Creative Industries business surveys. One of our key recommendations is to use standardised questions (e.g. from the PEC’s Creative Radar work, or from other surveys) that allow some degree of benchmarking. It is also important to consider the type of survey you are commissioning and who is most likely to respond. Online surveys might be inexpensive but run the risk of only picking up responses from the ‘noisiest’ participants, while telephone surveys, whilst expensive and taking longer, could capture a more representative group of businesses that might not otherwise do online surveys.

_______________________________________

Of course, not all useful types of research are detailed on this page, and not all useful pieces of research are referenced in this info pack. If you want to find out more we have compiled a long list of useful pieces of research and further reading on this topic

_______________________________________

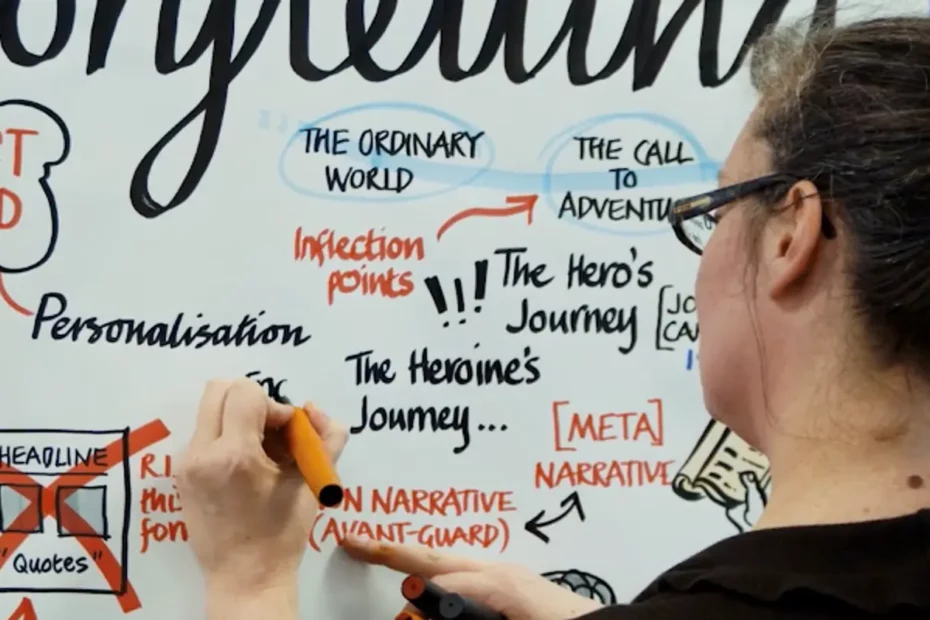

Image credit: Photo by Shirish Kulkarni from Clwstwr

Further research:

A First Look at Connections Between the Bresence of Creative Industries and the Wider Urban Economy (2020)

Description: Uses Business Structure Database to build a 21-year data set for UK cities exploring connections between the creative industries and wider economy.

Authors: Gutierrez-Posada, D. and Nathan, M. Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, CityREDI University of Birmingham and UCL.

https://www.pec.ac.uk/blog/a-first-look-at-connections

How to reference: Gutierrez-Posada, D. and Nathan, M. (2020) A first look at connections between the presence of creative industries and the wider urban economy, Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, CityREDI University of Birmingham and UCL.

Createch Activity in the UK (2021)

Description: An analysis of businesses at the nexus of creative and tech: who they are, where they work and what they need.

Author: Mateos-Garcia, J.

https://pec.ac.uk/research-reports/createch-activity-in-the-uk

How to reference: Mateos-Garcia, J. (2021) Createch Activity in the UK. Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and Nesta.

_______________________________________

Creative Industries Radar: Mapping the UK’s creative clusters and microclusters (2020)

Description: New approach to understanding clustering of UK creative businesses via the websites of 200,000 firms.

Authors: Siepel, J., Camerani, R., Masucci, M., Velez Ospina, J., Casadei, P. and Bloom, M. Multiple: Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and The University of Sussex

https://pec.ac.uk/research-reports/creative-radar

and interactive map available from:

How to reference: Siepel, J., Camerani, R., Masucci, M., Velez Ospina, J., Casadei, P. and Bloom, M. Multiple: (2020) Creative Industries Radar: Mapping the UK’s creative clusters and microclusters; Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and The University of Sussex

_______________________________________

Creative Places: Growing the creative industries across the UK (2021)

Description: Briefing paper setting out how policymakers can better support and understand the creative industries.

Authors: Burger, C., Easton, E., and Bakhshi, H. (2021). Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre

https://pec.ac.uk/policy-briefings/resilience-in-places-growing-the-creative-industries-across-the-uk

How to reference: Burger, C., Easton, E., and Bakhshi, H. (2021) Creative Places: Growing the creative industries across the UK; Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre

Insights from our industry champions: How policymakers can support local growth in the creative industries (2020)

Description: Write-up from panel with industry champions on impact of Covid-19, partnering with All Party Parliamentary Group for Creative Diversity

Authors: Easton, E. and Burger, C. (2020) London: Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre. Available from:

https://pec.ac.uk/policy-briefings/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-diversity-in-the-creative-industries

How to reference: Easton, E. and Burger, C. (2020), Insights from our industry champions: How policymakers can support local growth in the creative industries, Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre.

Meta-evaluation of Arts Council England-funded Place-based Programmes (2021)

Description: An evaluation of six ACE-funded place-based programmes pointing to actionable lessons to inform future place-based programme policy.

Authors: Lee, B., Nott, C.

How to reference: Lee, B., Nott, C. (2021) Meta-evaluation of Arts Council England-funded place-based programmes. Arts Council England and Shared Intelligence.

Mind the Gap: Regional Inequality in the UK’s Creative Industries (2019)

Description: Using DCMS Economic Estimates, this paper examines the distribution and growth of the Creative Industries in the UK at the regional level.

Author: Tether, B

How to reference: Tether, B (2019) Mind the gap: Regional inequality in the UK’s creative industries. London: Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and the University of Manchester.

Placemaking, Culture and Covid. Insights from our Industry Champions (2021)

Description: Insight and policy recommendations from creative industry champions on development and sustainability of ‘creative places’

Author: MacFarlane, T

https://pec.ac.uk/policy-briefings/placemaking-culture-and-covid

How to reference: MacFarlane, T (2021), Placemaking, culture and Covid. Insights from our Industry Champions, Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and Centre for Cultural Value

Place matters: Greater Manchester, Culture and ‘Levelling up,’ (2021)

Description: A consideration of how partnerships between local government and the cultural sector in Greater Manchester facilitated place-based responses to the impacts of the pandemic.

Authors: Dunn, B., Gilmore, A. Centre for Cultural Value, Available from: https://www.culturehive.co.uk/CVIresources/place-matters-greater-manchester-culture-and-levelling-up/

How to reference: Dunn, B., Gilmore, A. (2021) Place matters: Greater Manchester, Culture and ‘Levelling up; Centre for Cultural Value

Review of the Cultural Compacts Initiative. Arts Council England and BOP Consulting (2020)

Description: Review of the initiative concluding with five key considerations for ACE, stakeholders and the Compacts themselves

Authors: Moretto, M., Owens, P., Kuhn, R.

How to reference: Moretto, M., Owens, P., Kuhn, R. (2020), Review of the Cultural Compacts Initiative. Arts Council England and BOP Consulting.

The Austerity Decade: Local Government Spending on Culture (2021)

Description: Paints a nuanced picture of LA spending on cultural services after a decade of ‘austerity’.

Authors: Rex, B. and Campbell, P.

https://www.pec.ac.uk/blog/the-austerity-decade-local-government-spending-on-culture

How to reference: Rex, B. and Campbell, P. (2021) The austerity decade: local government spending on culture. London: Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, University of Warwick and University of Liverpool.

The European Capital of Culture: A Review of the Academic Evidence (2021)

Description: The first paper to synthesise research on the impact of the capital of culture programme on local authorities. It challenges some of the assumptions on the positive economic benefits for local economies.

Authors: Nermod, O., Lee, N. and O’Brien, D

How to reference: Nermod, O., Lee, N. and O’Brien, D (2021) The European Capital of Culture: A review of the academic evidence. London: Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, London School of Economics and University of Edinburgh.

The Relationships Between Cultural Organisations and Local Creative Industries in the Context of a Cultural District (2022)

Description: Explores interaction between large cultural organisations and creative businesses suggests interventions should focus on supporting more formal networks to see greater collaboration and positive economic impacts

Authors: Vartapetova, N., Fisher-Jones, H, Lam, C.

https://pec.ac.uk/discussion-papers/cultural-districts

How to reference: Vartapetova, N., Fisher-Jones, H., Lam, C. (2022). Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and AEA Consulting.

Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: A framework towards informing decision making (2021)

Description: Sets out the DCMS ambition to develop a formal approach to valuing culture and heritage assets

Authors: Sagger, H., Philips, J., Haque, M.

How to reference: Sagger, H., Philips, J., Haque, M. (2021). Valuing Culture and Heritage Capital: A framework towards informing decision making, Department of Culture, Media and Sport

When Policy meets Place: ‘Levelling up’ and the Culture and Creative Industries (2021)

Description: Part of the PEC’s Creative Places campaign, calling for targeted funding for creative micro clusters

Authors: Gilmore, A., Dunn., B, Barker., V, Taylor, M. (2021)

https://www.pec.ac.uk/blog/when-policy-meets-place

How to reference: Gilmore, A., Dunn., B, Barker., V, Taylor, M. (2021), When policy meets place: ‘Levelling up’ and the culture and creative industries; Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre

Place Based Approaches to Research Funding (2021)

Description: Part of the British Academy’s work on Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences and their role in supporting place based policy

Authors: The British Academy

https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/3242/Place-Based-Approaches-Research-Funding.pdf

How to reference: The British Academy (2021), Place based approaches to research funding

Hipsters vs. Geeks? Creative workers, STEM and innovation in US cities (2020)

Description: Research shows that those city regions are most innovative that have a high share of both creative and STEM workers, due to fusion of arts and science skills

Authors: Rodríguez-Pose, A and Lee, N

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103974/1/Cities_2020_PEEG_version.pdf

How to reference: Rodríguez-Pose, A and Lee, N (2020), Hipsters vs. Geeks? Creative workers, STEM and innovation in US cities

The Fusion Effect: The economic returns to combining arts and science skills (2016)

Description: This paper shows that firms combining these arts and science skills are more likely to grow in the future, are more productive, and are more likely to produce radical innovations.

Authors: Siepel, J, Camerani, R, Pellegrino, G, Masucci, M

How to reference: Siepel, J, Camerani, R, Pellegrino, G, Masucci, M (2020), The Fusion Effect: The economic returns to combining arts and science skills; Nesta

Supporting the Creative Industries: The Impact of the ‘Preston Model’ in Lancashire (2022)

Description: Sets out that the ‘Preston Model’ of strengthening supply chains through local procurement by anchor institutions, like local government and universities could support creative economy microclusters .

Authors: Whyman, P, Wright, A, Lawler, M, Petrescu, A

https://pec.ac.uk/research-reports/the-impact-of-the-preston-model-in-lancashire

How to reference: Whyman, P, Wright, A, Lawler, M, Petrescu, A (2022), Supporting the Creative Industries: The Impact of the ‘Preston Model’ in Lancashire; UCLan

The economic impact of universities: evidence from across the globe (2018)

Description: This paper argues that universities can be a crucial factor to local economic growth.

Authors: Valero, A and Van Reenen, J

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/90227/

How to reference: Valero, A and Van Reenen, J (2018), The economic impact of universities: evidence from across the globe; Economics of Education Review, 68. pp. 53-67

Mapping and examining the determinants of England’s rural creative microclusters (2022)

Description: Sets out opportunities for supporting development of creative industries microclusters in rural areas and towns, showing the importance of existing cultural institutions and local universities offering creative subjects.

Authors: Velez-Ospina, J, Siepel, J, Rowe, F, Hill, I

https://pec.ac.uk/research-reports/rural-creative-microclusters

How to reference: Velez-Ospina, J, Siepel, J, Rowe, F, Hill, I (2022), Mapping and examining the determinants of England’s rural creative microclusters; National Innovation Centre Rural Enterprise (NICRE), Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre

Blog: Levelling Up: how we’re helping UK businesses to build through IP(2022)

Description: Blog post by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) showing that intellectual property as an important driver of intangible assets and howhttps://pec.ac.uk/admin/entrie… the IPO can support regional growth through this

Authors: Intellectual Property Office (IPO)

How to reference: Intellectual Property Office (2022), Blog: Levelling Up: how we’re helping UK businesses to build through IP

Related Blogs

From Wales to the World: Why International Cultural Policy Needs a Future Generations Lens

This guest blog is from Professor Sara Louise Pepper, a member of our Global Creative Economy Counci…

10 facts about Creative Industries growth potential

Discover ten key findings from the report 'High-Growth Potential Firms in the UK's Creative Industri…

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.