It’s five years since Nesta first identified “Creative R&D” as a distinct and distinctive form of innovation happening inside the UK Creative Industries. Released whilst a new wave of public investments like UKRI’s Creative Industries Clusters Programme or the Audience of the Future Challenge were unlocking new experimentation at the interface of research, creative practice and emerging technologies, the idea of Creative R&D has spread widely in the years since. But many questions about Creative R&D remain unanswered.

I spend a lot of time thinking about those questions. At the National Gallery I’ve created an innovation lab, National Gallery X, with King’s College London to think about what Creative R&D can do for museums. As a Policy and Engagement Fellow at the Arts and Humanities Research Council, I’ve spent the last year helping scope the business case for CoStar, a proposed new national scale infrastructure in the Creative Industries. As a Masters student in innovation and public purpose with Mariana Mazzucato at UCL, I’ve tried to define what Creative R&D means in formal economic terms. And as part of a working group with fellow travellers in the arts and culture sector, I’ve worked on a Arts Council England funded report (coming soon) on the features, history and future of an expanding but extremely fragile ecosystem.

From all that and five years on from Nesta’s brilliant paper, three things are most apparent to me about the current state of Creative R&D.

The work is amazing

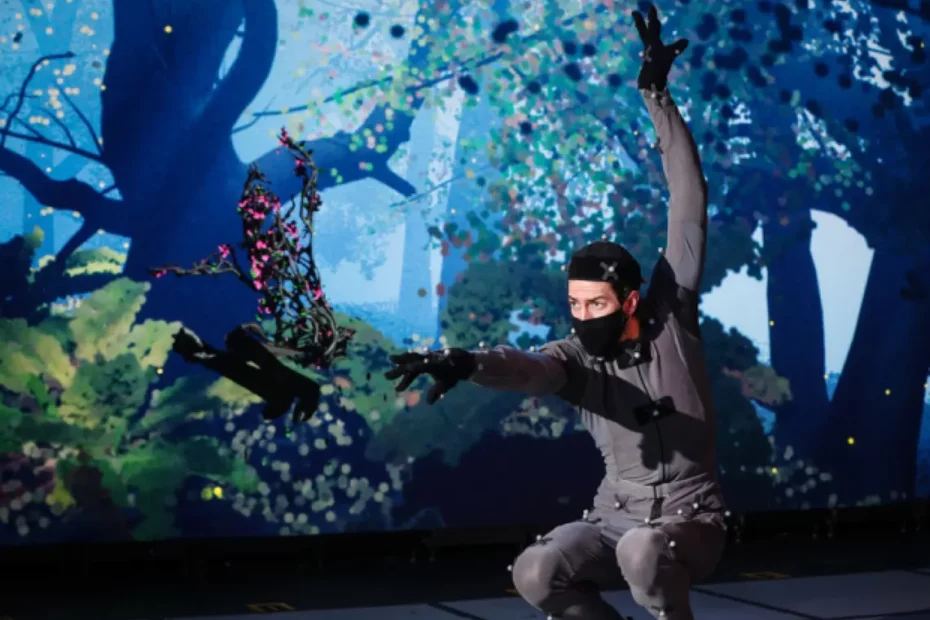

Before we get to existential concerns, let’s stop and celebrate the incredible work that happens at this intersection of creative practice, research and technology. The last year has seen amazing work reaching (and changing!) audiences in astounding new ways. Dream, part of the Performance Demonstrator programme in the Audience of the Future Challenge, showed an incredible new horizon for theatre as Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream was digitised through motion capture and recast into a magical virtual forest. Watched by over 60,000 people in just a few days’ performances, Dream redefined nearly all of the parameters of what “performance” could mean.

At the Gallery we’ve continued to probe how emerging technologies, research and our collection can come together in new ways. Our exhibition, Sensing the Unseen was formed through a radical co-creation process bringing technologists, poets, curators, sound artists and more together to create a show now on tour in Winchester Cathedral.

And working with our friends at Nesta and King’s College London, National Gallery X has run HOME-Zero, an in-progress commission where two creative teams, Love Ssega and Makers of Imaginary Worlds will develop experiences to helps catalyse a net zero carbon future, inspired by one of the greatest collections of art in the world. These are just a sliver though – across the Creative Industries and across the country, radical new futures are being imagined at the interface of art and technology.

Its form and history remain undefined.

Nesta’s original paper called for a redefinition of the economic definition of R&D by the UK government, following a broadening of terminology in the OECD’s Frascati Manual in 2015. The impacts of this have filtered into work such as the DCMS “R&D in the Creative Industries Survey” of 2020, which measured the gap both current and potential technical definitions lead to in our ability to measure innovations in the Creative Industries. In the last year AHRC Creative Economy Champion Andrew Chitty has doubled down on the economic impact such a change might make.

Whilst the economic case makes progress, the history of Creative R&D is beginning to be documented. One of last year’s best books was David Curtis’London’s Art Labs and the ‘60s Avant-Garde which told the story for the first time of what we can retrospectively identify as the first Creative R&D Labs in the UK. A brilliant story of remarkable creativity that enthralled an avant-garde public as it met reactions of disgust or disregard from funders, it builds on Catherine Mason’s history of early computer art, A Computer in the Art Room to provide a pre-history of today’s Creative R&D.

The alienation of this work from the “official” story of the UK’s cultural history remains apparent however. Lisa Tickner’s excellent 2020 history of London’s 1960s emergence as the centre of the global contemporary art scene, London’s New Scene notably makes no mention of the radical meetings of robotics and art happening in UCL’s computer science department in the work of Edward Ihnatowicz, or in the Drury Lane Arts Lab where a young David Bowie sometimes performed as a mime artist. That shows how much of the story of Creative R&D, and a sense of its importance, still remains to be told.

Its future remains uncertain

These are in many ways golden days for Creative R&D. With funding programmes like the Creative Clusters, Audiences of the Future and – hopefully – CoStar to come, there is significant money and opportunity flowing into an evolving national ecosystem. In the film and high-end TV sector, a wave of foreign investment driven by the expanding streaming market is seeing huge and high-profile builds of new studios, increasingly with facilities in Virtual Production and its associated technologies. In a piece of landscape analysis I carried out for UKRI with Professor Jonny Freeman from Goldsmith’s College, we identified nearly 130 studios across the country – from tiny to vast – which offered capability and capacity in relevant technology domains. This will grow and become more coordinated so there should not be a lack of places and spaces in which to create and research.

But whilst this remarkable rise of Creative R&D continues, so much remains fragile. Whilst the formal definition of R&D remains unchanged; whilst there is a critical dependency on central funding programmes to stimulate activity; whilst full histories remain undocumented, Creative R&D remains at some risk of not being what it could be: a great national superpower for the creative industry of the future. And whilst questions of how diversity and inclusion can be radically improved and how creative technology can work towards net zero, we still have many profound unknowns to work on. But in face of work like Dream and amidst programmes of the potential of CoStar, we should view these risks with hope. Five years on from Nesta naming Creative R&D, Creative R&D is growing up, and growing into something both magical and critical for what this country can do.

This blog was published as part of the PEC’s spotlight on R&D week which ran between 14-18 February 2022.

Related Blogs

From Wales to the World: Why International Cultural Policy Needs a Future Generations Lens

This guest blog is from Professor Sara Louise Pepper, a member of our Global Creative Economy Counci…

10 facts about Creative Industries growth potential

Discover ten key findings from the report 'High-Growth Potential Firms in the UK's Creative Industri…

Why London is investing in Creative Enterprise Zones

London Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan announces £2.2 million in new funding for Creative Enterprise Zones.

Research resources on Creative Clusters

We’ve collated recent Creative PEC reports to help with the preparation of your Creative Cluster bid…

What UK Job Postings Reveal About the Changing Demand for Creativity Skills in the Age of Generative AI

The emergence of AI promises faster economic growth, but also raises concerns about labour market di…

Creative PEC’s digest of the 2025 Autumn Budget

Creative PEC's Policy Unit digests the Government’s 2025 Budget and its impact on the UK’s creative …

Why do freelancers fall through the gaps?

Why are freelancers in the Performing Arts consistently overlooked, unseen, and unheard?

Insights from the Labour Party Conference 2025

Creative PEC Policy Adviser Emily Hopkins attended the Labour Party Conference in September 2025.

Association of South-East Asian Nations’ long-term view of the creative economy

John Newbigin examines the ASEAN approach to sustainability and the creative economy.

Culture, community resilience and climate change: becoming custodians of our planet

Reflecting on the relationship between climate change, cultural expressions and island states.

Cultural Industries at the Crossroads of Tourism and Development in the Maldives

Eduardo Saravia explores the significant opportunities – and risks – of relying on tourism.